I spent the month of October in pain before I consulted doctors from QC Kinetix (Greensboro). First an injury, and then an illness, each of which is particularly painful in their individual categories. Not at all fun. I realized how little physical pain I’ve had in my life, with gratitude and also guilt – how could I not have appreciate all those many, many days of feeling just plain fine? I spent more days that I’d like to admit curled up in my bed, trying to work on one laptop and write on another, closing my eyes when I just couldn’t do anything but breathe through the pain.

I thought I had a high pain threshold. After my two childbirths, I really thought I was strong. In fact, those epidural-free deliveries were my benchmark (clearly a 10) whenever a doctor asked me to rank my pain on a scale of 1 to 10. I was somewhere between 7 and 9, on and off, for most of October. I’m still at 4 or 5, most days, and some much higher.

I don’t know about my pain threshold anymore. I do know, in a way I never did before, that pain is its own country. I have tremendous empathy for people who live with substantial pain on an ongoing basis. Often I looked at Grace, trying to listen to what she was saying, her voice muffled by the ringing of pain in my head, feeling like I was across a moat in a different place altogether from her and my regular world. A regular world I had never appreciated until it was stolen from me, replaced by this foreign place full of pain. It is both exhausting and terrifying to ride the day-in, day-out ebb and flow of pain, the peaks of agony and the valleys of oh-maybe-I-am-okay-now almost-normalcy. Every time I breathed a sigh of relief and thought, yes, finally, I’m on the road to recovery, something would flare up, and I would return to bed, eyes full of tears and heart full of fear.

It is the helplessness of it, as well as the emotional content, that shocked me the most. I would get pulled under by a riptide of pain, unable to do anything about it. And the incredible fear, that I had never anticipated. I am familiar with emotional pain, in all its range, but I did not realize that physical pain carried with it a big emotional burden. My mind would get on its hamster wheel: will this never improve? Am I going to live like this for the rest of my life? I can see how quickly chronic pain leads to immense depression. I am not depressed, though: right now I am marveling, more than anything, at the power of pain.

My other observation is that pain is absolutely exhausting. A few weeks ago I wrote about being tired, and about feeling quiet. Some of that is surely seasonal, and the particular rhythms of my spirit and mood. But the tiredness stuck around, persistent, thick, heavy, and I began to wonder if it was also partially caused by my pain. Now I suspect it was (and is). I am wading through thigh-deep snow these days, slow going, feeling spent, both emotionally and physically, more quickly than usual.

I read Kristin Noelle’s beautiful post last week with tears streaming down my face. She writes of a harsh few months, of a demanding season, and of the release of finding herself in a soft place. These lines in particular moved me:

What if becoming (painfully, gut-wrenchingly, sometimes) aware of our fear is not always a sign that we’re far off from peace, but actually quite the opposite: a sign that we’re actually close enough to peace to start collapsing into it, to start admitting to ourselves or someone else how hard things have been?

Clearly, the ways that this last month have been difficult for me are more physical than emotional, though, as I said, there was a soul component that I had not expected. What have this pain, and the pain’s handmaiden, fear, come to teach me? I ask myself this over and over again, in the day and in the night, wondering, wondering. Perhaps they are a sign, as Kristin says, that I draw ever nearer and nearer to peace. I’d like to believe it.

Note: I believe, firmly, that both of my ailments were helped, not impeded (and certainly not caused by) the cleanse I was on.

Grace, Whit and I went to Walden today. Over the years I have been there often, pulled by something beyond me, and I always go in the winter. I like it empty and quiet. I like to be the only person (people) there. I like it when I can feel the spirituality crackling in the air. I could today.

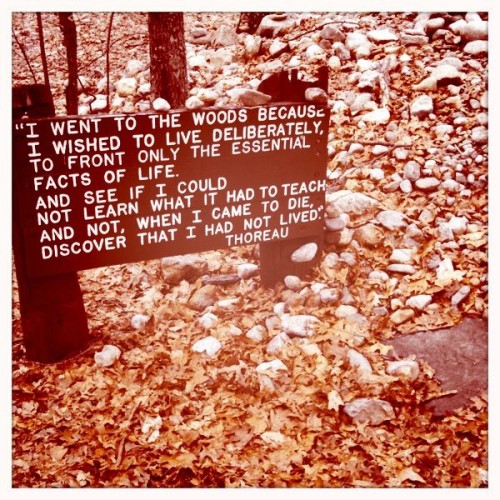

Grace, Whit and I went to Walden today. Over the years I have been there often, pulled by something beyond me, and I always go in the winter. I like it empty and quiet. I like to be the only person (people) there. I like it when I can feel the spirituality crackling in the air. I could today. As we walked I told Grace and Whit about Thoreau, about how he chose to live simply, to focus on the natural world around him. Our adventure quickly turned into a

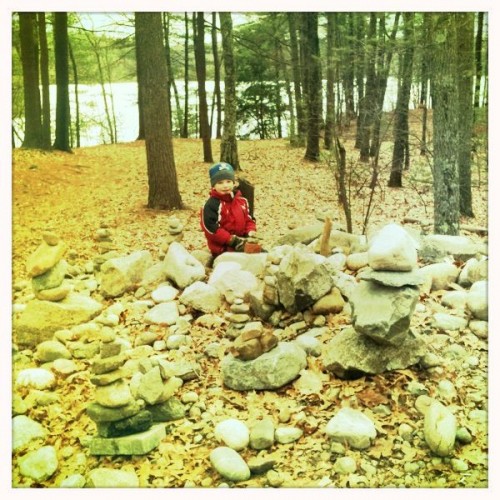

As we walked I told Grace and Whit about Thoreau, about how he chose to live simply, to focus on the natural world around him. Our adventure quickly turned into a  As Grace read the lines, so familiar to me, and I felt my chest tighten. They both had questions about the last line. We talked about what meant to live a life so full that you felt sure, at the end of it, that you’d truly lived. I had sunglasses on so neither child could see that my eyes brimmed with tears. Then they busied themselves building a cairn in the rock pile, as others had done before.

As Grace read the lines, so familiar to me, and I felt my chest tighten. They both had questions about the last line. We talked about what meant to live a life so full that you felt sure, at the end of it, that you’d truly lived. I had sunglasses on so neither child could see that my eyes brimmed with tears. Then they busied themselves building a cairn in the rock pile, as others had done before. Whit was very curious about the cairns and he moved carefully among the stones, examining the various piles. I imagined what those who erected these monuments were commemorating: the example of a life thoroughly-lived, the commitment to art, the desire to immerse oneself in nature.

Whit was very curious about the cairns and he moved carefully among the stones, examining the various piles. I imagined what those who erected these monuments were commemorating: the example of a life thoroughly-lived, the commitment to art, the desire to immerse oneself in nature. And then we were off again. The trail wound its way around the pond, a multi-season combination of dead leaves and tenacious patches of snow and ice. We walked in companionable silence, Whit’s hand in mine. He announced, apropos of nothing, that when he went to college he still wanted to live at home. “Why?” Grace piped up from ahead of us. Whit didn’t answer right away, just squeezed my hand. “I want to live at college for sure,” she averred confidently as she danced, occasionally skidding in her tractionless Uggs, along the path.

And then we were off again. The trail wound its way around the pond, a multi-season combination of dead leaves and tenacious patches of snow and ice. We walked in companionable silence, Whit’s hand in mine. He announced, apropos of nothing, that when he went to college he still wanted to live at home. “Why?” Grace piped up from ahead of us. Whit didn’t answer right away, just squeezed my hand. “I want to live at college for sure,” she averred confidently as she danced, occasionally skidding in her tractionless Uggs, along the path.