This weekend was glorious: finally, full sunshine, open windows letting in soft spring air, children biking and running until they were exhausted, and dinner at a restaurant so nearby that Matt and I could walk there through the dusky spring evening.

Saturday I spent five hours in the car scanning unfamiliar radio stations. I’ve written before about the power that songs have in triggering memory for me; for hours, it was like spinning an old-fashioned rolodex and seeing what was written on the card that it fell open to. In many cases the words to songs rose up out of some deep reservoir of memory: the words seemed to be carved indelibly on some scroll hidden deep in my consciousness. I had no idea I knew the words to a song, often, until I was singing along to it.

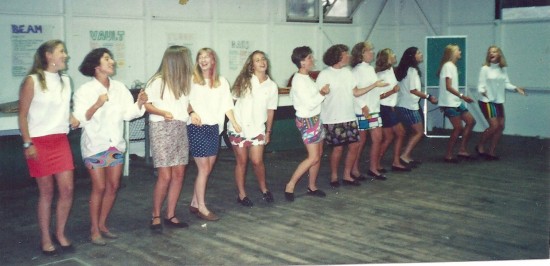

I’ve realized that my years at camp are full of musical memories. I wrote about how Like a Prayer will always remind me of being 16 years old and dancing down the dusty dirt aisles of the camp theater, the sheer joy of movement overtaking me. That song will always, every single time I hear it, remind me of a special, influential friendship and of the fact that I used to love to dance. One camp tradition that I loved was that each Sunday one unit would perform a song that they’d practiced all week. These were themed and though I can’t be sure I’m remembering right, I think there were also poems and quotations read aloud. One year my bunkmates and I sang Landslide, and yesterday, The Logical Song by Supertramp came on and I remembered that that was one too. Then the Go-Gos came on, and I remembered my Assistant Counselor year, when my 11 peers and I got up during one camp assembly and sang Our Lips Are Sealed.

I just cannot wait for Grace to experience camp, and I hope that the place is as important to her as it was to me, magical and grounding at the same time.

I just cannot wait for Grace to experience camp, and I hope that the place is as important to her as it was to me, magical and grounding at the same time.

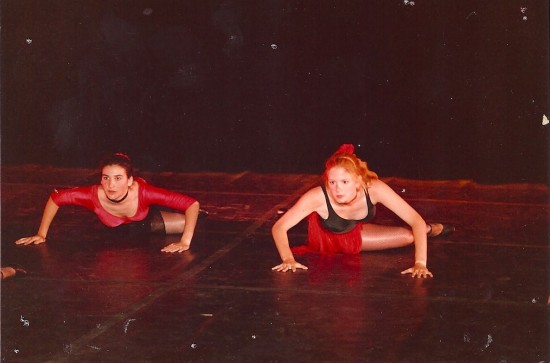

The Soup Dragons came on, singing I’m Free, and I thought about another time when dancing was important to me. Senior year at Exeter I participated in the dance concert instead of doing a sport. My dear friend C, a rare real, substantive friend in those years, and I did it together. We choreographed several pieces, one of which was to I’m Free. In the annals of embarassing photographs, here’s one from another piece (for I’m Free we wore cut-offs and tie-dyed shirts, and I do not have a picture of it).

And then a couple of songs sent me back to college, specifically to my little quad in the sky. The Freshman, by Verve Pipe, Lightning Crashes, by Live, and Whenever I Call You Friend, by Kenny Loggins, each carried specific and visceral memories. Whenever I Call You Friend, in particular, reminds me of when I had a broken leg and my wonderful roommates took it upon themselves to dance and sing to entertain me. In the photograph below they are serenading me, and I remember leaning over to grab my camera, and taking the picture, remember how I was laughing so hard that I could barely hold the camera straight.

And then a couple of songs sent me back to college, specifically to my little quad in the sky. The Freshman, by Verve Pipe, Lightning Crashes, by Live, and Whenever I Call You Friend, by Kenny Loggins, each carried specific and visceral memories. Whenever I Call You Friend, in particular, reminds me of when I had a broken leg and my wonderful roommates took it upon themselves to dance and sing to entertain me. In the photograph below they are serenading me, and I remember leaning over to grab my camera, and taking the picture, remember how I was laughing so hard that I could barely hold the camera straight.

And then REM’s Night Swimming brought me back to a spring evening, not altogether unlike this one in Boston, when I walked from my freshman dorm to meet a boy for a first date. The air was thick with the smell of magnolias, the sky perfect, hydrangea blue; we were in the weeks when Princeton is at its most beguiling. I walked through the junior and senior dorms, gothic facades on either side of me, feeling vaguely intimidated to even be in these spaces that were still foreign to me. As I approached the room where I was going, the lead-paned windows were all open and REM’s Night Swimming wafted out into the early evening. I felt anticipation and nerves, was somehow aware, deep in my consciousness, that I was about to step into a relationship that would be one of the most important of my early adulthood and most formative of my life. I’ve never heard that song since that night without thinking of that walk, and that sense of promise, the tangible presence of the future right in front of me.

And then REM’s Night Swimming brought me back to a spring evening, not altogether unlike this one in Boston, when I walked from my freshman dorm to meet a boy for a first date. The air was thick with the smell of magnolias, the sky perfect, hydrangea blue; we were in the weeks when Princeton is at its most beguiling. I walked through the junior and senior dorms, gothic facades on either side of me, feeling vaguely intimidated to even be in these spaces that were still foreign to me. As I approached the room where I was going, the lead-paned windows were all open and REM’s Night Swimming wafted out into the early evening. I felt anticipation and nerves, was somehow aware, deep in my consciousness, that I was about to step into a relationship that would be one of the most important of my early adulthood and most formative of my life. I’ve never heard that song since that night without thinking of that walk, and that sense of promise, the tangible presence of the future right in front of me.

And then, as I neared home, poetically, Southern Cross came on. I’ve always loved CSN(Y), and this song is one of my favorites. I thought instantly of the summer of 1998, when Matt and I spent 6 weeks in Africa. We had known each other only a month or two when we planned the trip; I think my parents probably thought I was coming home in a bag. We climbed Kilimanjaro and on night before the summit ascent it was crystal clear and gorgeous (not so the night we summitted – white-out blizzard conditions). We could see both the Southern Cross and the Big Dipper in the sky which, our guide told us in his lilting, accented voice, was very rare. Only possible right near the Equator. We both looked up, spellbound at the enormous sky above us, at how far we were from everything we knew. And yet, at that moment, I’m certain we both felt at home. “For the first time you understand … why you came this way.” And we did.

What songs trigger important memories for you?

This was one of the most special days of my life. One of our days at Disney, Grace and I snuck away to go to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter. We were both spellbound. I have never been somewhere more crowded – honestly. Harry Potter made walking through the Magic Kingdom seem like an amble on a deserted beach. But still…. still. It was absolutely magical. We walked around Hogsmeade, bought a wand, drank Butter Beer, explored Hogwarts castle, and rode twice on the Flight of the Hippogriffs (above, photo taken from car in front of us). I don’t like roller coasters and neither do either of my children (coincidence? perhaps not) but this was a nice, not-scary ride that we went on twice.

This was one of the most special days of my life. One of our days at Disney, Grace and I snuck away to go to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter. We were both spellbound. I have never been somewhere more crowded – honestly. Harry Potter made walking through the Magic Kingdom seem like an amble on a deserted beach. But still…. still. It was absolutely magical. We walked around Hogsmeade, bought a wand, drank Butter Beer, explored Hogwarts castle, and rode twice on the Flight of the Hippogriffs (above, photo taken from car in front of us). I don’t like roller coasters and neither do either of my children (coincidence? perhaps not) but this was a nice, not-scary ride that we went on twice.

With special thanks to

With special thanks to