I didn’t have the best Easter I’ve ever had. On Saturday afternoon I began feeling sick, a nausea that intermittently escalated and ebbed. By 7 I was in bed with a fever, trying hard not to throw up. Sunday I woke up feeling somewhat better, though I remained vaguely carsick all day long. This made me short with the children and with Matt in the morning, barking at them when I felt frustrated, annoyed at myself that I could not avoid this behavior. Everything felt frayed and difficult by 8:30 in the morning.

At church, ease floated down to rest on my shoulders. Sitting there, in a place that has held so much of my history – my sister’s marriage, both Grace and Whit’s christenings (each, actually, on Easter weekend) – I exhaled. I sang the songs I know by heart, their lyrics rising from some deep, hidden reservoir of memory, from the years at St. Paul’s Girls’ School. My eyes filled with tears as I remembered the three grandparents I have lost, particularly Nana, my maternal grandmother, who always cherished Easter above all holidays. I sank deep into the familiar cadence of the prayers before communion. I felt gladness enter my heart, and in its wake, gratitude.

But as soon as we left the church, into the almost startling brightness of the day, into the sudden full-bloom of spring, the grace I’d felt in the pew sloughed off and my agitation rose to the surface again. I felt nauseous, I felt tired, I felt cranky. We had a lovely egg hunt at my parents’ house, with both my godsister and her family and my cousin and her boyfriend. And then we had a relaxed, comfortable lunch at our house, my father and mother full of fascinating stories and observations from the trip to Jerusalem from which they just returned yesterday.

The day was nothing short of delightful, with only a couple of whiny kid moments to mar its gleam. And I felt the person – the mother, wife, daughter – I want to be floating in the room, sometimes within reach, sometimes not. The presence and peace that I grasp for so clumsily was just in my palm and then jerked away again, replaced by an unease of the soul that manifests as physical discomfort.

After lunch my nausea rose up in my throat again, threatening, and I climbed back into bed. I felt demoralized, frustrated: after so many years, after so much trying, how can I still stumble, fall back into these traps, these old ways of being? Didn’t I just write, a few days ago, that the black emotions can blow through, like a squall, and still leave me with the memory of a beautiful day? I know what this agitation is about, I think: it is hiding, it is refusing to stare into the sun. It is my attempt to evade the pain that is an inextricable part of truly engaging in my life.

But oh, what irony there is in this, I see now. The pain I feel in knowing how much I’ve missed, in realizing how much these avoidance behaviors have cost me is so much keener than the pain of looking my life in the eye. I know this as well as I know my own name. Many days now, like last week, I can acknowledge the irritation that comes as regularly as a tide, and let it pass. On Easter I could not: I got tangled in it.

“Healing,” Pema Chodron reminds us, “can be found in the tenderness of pain itself.” I read this last Easter, on Katrina Kenison’s gorgeous blog, and the words returned to me today. The pain of living my life, of accepting the passage of time, of embracing my own wounded heart: these are the kinds of pain that Pema speaks of. The awful, toxic pain of regret, however, carries no tenderness. There is no healing in avoidance, in the way I felt for big swaths of Easter Sunday.

What is Easter if not the day of renewal, rebirth, resurrection? Yes, I squandered a lot of it being crabby and irritable and short-tempered. Yes, I drove myself to sobs alone in my room thinking: I will never have another Easter egg hunt when Grace is 8 and Whit is 6. I don’t know exactly why I felt this way on Easter, a day I’ve always loved deeply. I know that instead of attacking myself for this waste, lying in the dark, crying, as my stomach roiled as though I’m at sea in a storm, I should instead embrace what Easter means, believe in the return of my peace. I am trying.

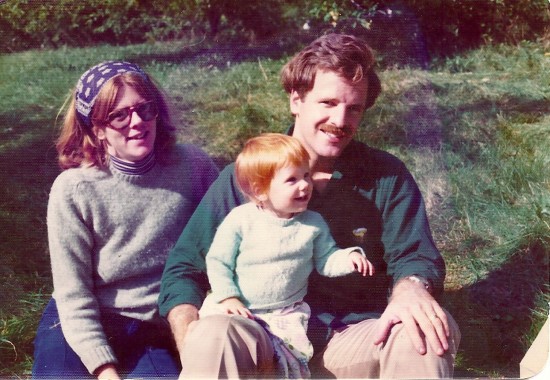

Happy Mother’s Day, Mum.

Happy Mother’s Day, Mum.

I started an essay years ago with this sentence:

I started an essay years ago with this sentence: