I have said before, and I will say again, that demonstrations of independence, bravery, and kindness by my children make me prouder than conventional achievement. Recently I have had an opportunity to see Whit in particular wade into these waters past where he is comfortable. It has been both nerve-wracking and fabulous to watch him swim.

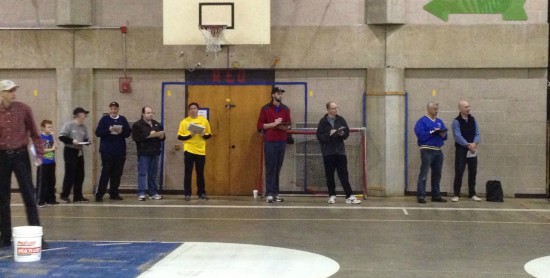

A few weekends ago, I took Whit to baseball tryouts. Little league tryouts. I live in a famously liberal town. Whit has never played baseball before in his life. Never. Both of us were entirely, absolutely unprepared for what we encountered in that school gym. The boys had numbers pinned to their backs and went through their paces, one a time. Sprinting. Catching. Throwing. Batting. All while a lineup of adult men – the coaches of the various teams – watched, scribbling notes on clipboards as they did so. I looked around, bewildered, wondering if I’d mistakenly stumbled into spring training.

As Whit stood in line to do his timed sprint, the first of the various drills, I caught his eye across the gym. He looked somewhere between terrified and mortified. My stomach twisted. For an hour and a half I watched him in the various activities, feeling relief and anxiety rise and fall like tides inside of me.

There was no complaining, there was no posturing, there was no giving up. He just found himself in an unfamiliar and intimidating situation, put his head down, and did his best.

Tryouts reminded me of this fall, when, after an uncomfortable encounter with our head of school, Whit walked into the gate the next morning, looked her in the eye, and said, “Good morning.” He did it again the next day. And the next. And each morning, walking next to him, I was pierced with both powerful pride and an intense awareness of how much that eye contact and “good morning” took from him. And for many days I told him how I felt when I tucked him in. He looked at me, eyes gleaming in the dim light of his room, and I could tell that he felt acknowledged. That he felt seen.

These experiences remind me of some of my dearest wishes for my son:

May he always look life in the eye and not flinch. May he always welcome what is to come with open arms. May he know that to do the best he can is all there is. May he not shy away from trying, even when he doesn’t know if he will succeed.