One of my friends from business school lost a brother in 9/11. My friend, his wife, and the rest of his large family started a foundation in their brother’s name. On Sunday I wore a tee-shirt from one of their fundraisers to go running. I didn’t have time to shower when I got back, and so, hours later, when I bathed the kids, I was still wearing it.

“Who is the man whose name is on your tee-shirt, Mummy?” asked Grace idly, tracing her fingers through the bubbles in the bath. I swallowed. Both she and Whit know in general terms about “when the planes flew into the buildings” but they don’t know more than that. Were they ready?

“Well,” I began, “Remember how we talked about the day when the planes flew into the buildings? A friend of mine’s brother was in one of the buildings, and he died that day.” I paused. Both Grace and Whit were quiet.

“The pilots flew the plane into the building?” Grace looked at me.

“Well, no. The bad guys on the plane took over the cockpit.”

“How? And what did they do to the pilots, Mummy?”

“I think they used force to get into the cockpit. And the pilots,” I looked straight at her, hesitating. “Well, they died.”

Grace’s mouth formed a silent “o” and she looked down at the bathwater.

“Why didn’t your friend’s brother get out of the building, Mummy?” If Whit were any child I’d have sworn he wasn’t listening, so busy did he seem with the bathtub dinosaur toys. But clearly he wasn’t missing a word.

“Well, Whit, they couldn’t get out.”

“Do you think they felt it when the plane hit the building? Did they feel it when the building fell down?’

I was at a loss for words. How to convey this day, so enormous, so terrifying, in a gentle, age-appropriate way?

“I don’t know what they felt, Whit.” I spoke slowly, trying for gentleness. “I wasn’t there.”

The conversation went on to talk about security at airports, and how things are much different now than they were before 9/11. Grace and Whit wanted to know a lot about the bad guys, who they were, how it is that they killed themselves for their countries. I had to be very clear that these people were not heroes, despite this act. Based on their very specific questions, and the way that they wouldn’t let the topic go, I decided that they deserved real answers. By the time we were finished talking, both kids were dry and in their pjs. This was a long, detailed conversation, and left us – as most conversations in my life do – with more questions than answers. What is it to really hate a people, when you don’t know them? How do you life with intense fear, as the people on the planes must have felt? Who was Osama Bin Laden and why was he so angry? What does it feel like to feel the ground beneath you fall out, and to tumble to the ground?

Grace wanted to pray for the people who died in 9/11 when she was going to sleep, and so we did. And I woke up to the news that he had been killed. In my Monday morning oblivion I didn’t even realize the coincidence (or not) until Kathryn emailed me to point it out. And since that moment goosebumps have buzzed up and down my arms and neck. A reminder of the great river of humanity, both seen and unseen, that we all travel in. Everything is connected.

All day long I’ve been reading messages, tweets, blog posts, and articles about Bin Laden’s death. This morning, driving from school to the grocery store, I listened to NPR reporting on the massive celebratory throngs that has sprung up all over America last night. They played a recording of BU students belting out America the Beautiful. They compared the mood of the crowds to the emotional, triumphant reaction to the Red Sox winning the World. Series. What?

And all day, I’ve felt ambivalent about this. I’m not unhappy that Bin Laden is gone, though I am wary about celebrating an active murder no matter what the reasons behind it. But I think my ambivalence is more general: why are we celebrating anything about an event, and an ongoing situation, so full of pain, misunderstanding, and sorrow? While I can definitely see the justice in this outcome, I feel sad, not joyful, not proud, about this reminder that our world is most certainly not in a place of compassion and empathy.

Last night, as I tucked Grace into bed, she asked me again about the planes and the buildings. It was clear from her tone that she had been thinking about it all day. “What happened to the bad guy?” she asked me, and the hairs on my arms stood up. I looked straight at her, deciding in that moment she deserved, again, a real answer.

“Well, Gracie, he actually died yesterday.” Her eyes widened, the whites glowing in the dark of her room. “The US military found him and killed him.”

“They did?” She asked faintly, curling her beloved brown bear more tightly into her chest.

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Well, they wanted to keep America safe and make sure he couldn’t plan anymore attacks. And I guess they wanted to punish him for having caused so much pain.”

“Oh.” She was quiet. “Are we supposed to be glad about that, Mummy?” Her voice wavered.

“I don’t know, Grace.” I hugged her, smelling the shampoo I was her hair with every night, hearing the achingly familiar lullabyes from her CD player. “I don’t know.”

Parrot tulips, pale pink and green.

Parrot tulips, pale pink and green. Bricks, outside our front porch, colored in chalk in the rain by Grace and Whit.

Bricks, outside our front porch, colored in chalk in the rain by Grace and Whit. Two eight year old girls climbing onto the roof of a play structure at the park on an early spring day.

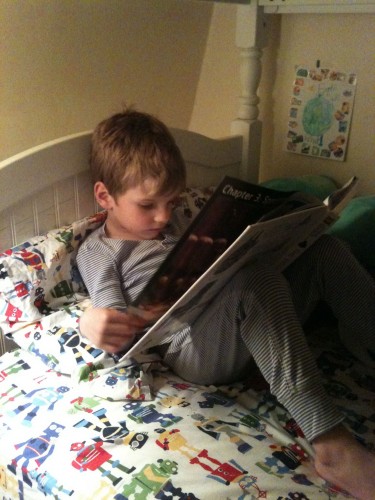

Two eight year old girls climbing onto the roof of a play structure at the park on an early spring day. Whit, reading quietly in bed (after he protested my effort to put him to bed at 6:52, I allowed 15 minutes of solo reading).

Whit, reading quietly in bed (after he protested my effort to put him to bed at 6:52, I allowed 15 minutes of solo reading). Sunrise from the air over New York, 6:30am, last week.

Sunrise from the air over New York, 6:30am, last week. Yesterday afternoon Grace asked me to play American Girl dolls with her. I told her I couldn’t right that minute, but that we could before bed if she wanted to, though she’d have to forgo TV. No problem, she enthused. Later, as we were playing, she mentioned that most of her friends at school don’t play American Girl anymore, and I felt a surge of emotion – some combination of panic and sadness, the steamroller of this life roaring in my ears as it flies past.

Yesterday afternoon Grace asked me to play American Girl dolls with her. I told her I couldn’t right that minute, but that we could before bed if she wanted to, though she’d have to forgo TV. No problem, she enthused. Later, as we were playing, she mentioned that most of her friends at school don’t play American Girl anymore, and I felt a surge of emotion – some combination of panic and sadness, the steamroller of this life roaring in my ears as it flies past.