My friend and HBS classmate Chris and I have connected through our blogs in the last year. I did not know Chris at school, though I knew who he was, and my impression was that he was very bright and very authentically happy. I assumed he would have no interest in someone with as little to offer in the HBS classroom as me. It’s been a substantial joy, then, to have gotten to know him through his words over the last months. He’s bright and happy, yes, but also thoughtful, wise, honest, and open. Click over and check him out – I highly recommend it.

Last week Chris emailed me about my most recent blog post, beginning an exchange that ended up lasting much of the Thanksgiving holiday. We touched on optimism, the underrated virtues of melancholy, and the conundrum of memory. Here’s how the conversation went:

Chris: In this morning’s blog post, you quoted the following:

“We like to think that life is joy punctuated with pain but it’s not. Life is pain punctuated with moments of joy.”

The optimist in me wants to disagree with Kate about the joy/pain balance of life, but the pessimist in me senses that she is right. Perhaps it doesn’t matter, really, what the equation is, as long as we appreciate the joy and it sustains us through the pain. Of course everybody’s particular calculus is different, their balance of happy and sad, light and shadow individual. It’s no secret that mine leans towards shadow.

I think it’s interesting how our different personalities impact how we see the joy/pain balance of life. You say that you lean towards the shadow. In contrast, I’m a natural optimist with a preternatural level of happiness that my wife describes as well-nigh oblivious. And that’s how most people think of optimists—as happy and possibly naïve.

Yet you’re different. You’re an optimist, but it seems like you feel like your optimism is mistaken. How do you reconcile that inner conflict?

Lindsey: I don’t think I’m a pessimist. I think I am an optimist with a melancholy heart. A melancholy optimist. Perhaps I am misusing all of these words, but I don’t wake up every morning sure that the worst case is going to happen. Far from it. I guess I do have guarded optimism, and a persistent fear of being disappointed, but more often than not that fear isn’t enough to keep me from hoping.

In fact hope is something I’ve thought a lot about. I think it’s slippery, because I do think one of the keys to joy – happiness, peace, however you think about a pleasant life – is not being too attached to specific outcomes. It is in the dissonance between those ideals and reality that a lot of sadness happens, I think. And so my question with hope is how to avoid it hitching to a very specific result … does that make sense?

Chris: It makes perfect sense. That’s the Stockdale Paradox in a nutshell (link). Jim Collins wrote about it in “Good to Great,” which I think is one of those books that as HBS grads we’re legally obligated to quote on a regular basis. Collins formulated the Stockdale Paradox based on the story of how Jim Stockdale survived the POW camps in Vietnam despite being repeatedly tortured and mistreated. The paradox is as follows:

You must retain faith that you will prevail in the end, regardless of the difficulties.

AND at the same time…

You must confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.

The first part of the paradox is all about optimism. You have to be optimistic about life, if only because life without optimism is hardly worth living. After all, we are all going to die, and most of us will suffer horrible, debilitating, and expensive illnesses before the grim reaper claims us. The lucky ones die prematurely in accidents that bring instant death.

But a simple-minded optimism doesn’t work either. The second half of the Stockdale Paradox comes into play because Stockdale noted that it was the optimistic prisoners who said things like, “We’ll be out of here by Christmas” who died first, largely because the realities of the situation shattered their delusions, leaving them broken and vulnerable.

To some, it must seem like a cruel joke—without hope, life isn’t worth living, but that very same life has a nasty tendency to dash your hopes.

The way I deal with it is to hope for the best, but prepare myself for the alternative. I’ve spent my entire career in the startup world, living on the hope that I’ll be able to build a successful startup. Yet at the same time, I know that the vast majority of startups fail, and that there is decent chance that I’ll go through my entire career without experiencing a life-changing “liquidity event”. I’ve even written about the math in greater detail here: http://chrisyeh.blogspot.com/2010/07/entrepreneurship-is-about-happiness-not.html

The other nuance is that I focus on process rather than outcome. I’m a pretty avid sports fan, and while I love to win, I know that luck plays a major role. The best we can do is to make the right plays. If the best play is to throw a long pass hoping for a touchdown, you should throw that pass, even if you know there’s a chance it will be intercepted. Nobody’s perfect. But if you play the game the right way, you’ll give yourself the best chance to win—in sports as well as in business and life.

Does your melancholy tend to come when you get disappointing results, or when the outcome is still in doubt? I think the answer makes a big difference.

Lindsey: Two thoughts. The first is that my melancholy is more a basic orientation towards the world – in fact sometimes I think melancholy is just another way of thinking about/talking about sensitivity. I am wired in a way that makes me hyper aware of the sadness in every situation as well as the joy. And my “melancholy” is about one thing and one thing only, which is the irrefutable and unstoppable passage of time. This is so bittersweet to me that it sometimes is truly unbearable. That we won’t have any of the past moments back haunts me. So I don’t know that my melancholy comes in advance of results or because of doubt … it’s kind of just the backdrop against which my whole life is lived.

The second is your point about process and outcome, which I think is critical. I’m working on a memoir which is about an early 30s “crisis” in which I realized that the whole way I approached the world was flawed. I’m guided by the famous Carl Jung quote, “We cannot live the afternoon of life according to the program of life’s morning; for what in the morning was true will in evening become a lie.”

But your comments about process and result, and sports, make me realize that that is another way of saying the same thing. I’d always lived focused almost entirely on the next hurdle I had to clear, the next accomplishment I had to accrue. This is a very simple way to determine your direction, and it worked well for me for years. But there comes a time in life when there is no “next thing” (I had the two Ivy League degrees, the two kids before 30, etc) and at that point that entire mode of engaging with the world collapses. In your terms, the primacy of the result falters, and then we have no choice but to look at the process instead.

Chris: Your sensitivity to the passage of time really strikes a chord with me. I’ve always been sensitive to time’s one way arrow as well. From a young age, I was very conscious of the passage of time. I remember being 11 years old and thinking, “I’m almost through my childhood. I wish I could stop time now, because I know things will never be this simple and easy again.”

When I was a freshman in college, I remember staying up all night the final day before they kicked us out of the dorm, wanting to squeeze out every last drop of time, knowing that we’d never be assembled as a group again. I’m always reminded of a line from the Eagles’ “Take it Easy.”

“We may lose or we may win / But we will never be here again.”

I find myself saving the artifacts of my life—old ticket stubs, worn out t-shirts, even holiday cards. My wife is far less sentimental and tosses them in the garbage immediately. I like to keep them as talismans which allow me to travel back in time via memory. I’ve been blessed or cursed with a near-photographic memory (it sure came in handy when we were in school together!), which means that simply looking at a ticket stub can recall an entire evening. I’m afraid to throw things out because without them, I might now be able to call up those memories.

It might be that this hoarding of memories explains how I’m able to escape that melancholy. By putting the symbolic weight of my memories into external objects, I’m able to forget about the ticking of the stopwatch. What kind of tricks does your memory play on you?

Lindsey: I’ve thought (and written) about memory a lot. What strikes me, as I run through my own most prized and cherished memories, is how often they are not from the Big Days but, in fact, from the most mundane, regular days. How the things I hold most dear are often things that happened in the grout between the tiles of life’s big experiences. I can think of times in my life, very few, where I have been utterly present and simultaneously aware that I’m living something formative, special, important. Mostly, though, it’s after the fact that I realize how moving or powerful an experience was, and then I find myself wishing I had been more conscious as I lived it.

I’m fascinated by the way that the mind curates our memories, and by why it is that we remember what we do (and how). Anne Beattie has a beautiful line that I think of often: “People forget years and remember moments.” This truth, and the pattern that I can now recognize in how my most meaningful experiences are often cached in very ordinary experiences, both contribute to my almost-obsessive focus on trying to be more engaged in, aware of, and present to my own life. If I am not even paying attention to the mudane, there is no hope I will be able to see the magic.

Chris: I love the last sentence. In some sense, we all walk between Scylla and Charybdis when it comes to our memory. On the one hand, we must be present in the moment, or we’ll miss those special moments. On the other hand, we build our memories of those special moments like an oyster builds a pearl—with layer after layer of remembrance and rumination. Just think of how many times you’ve told your favorite stories from childhood—each retelling or reconsideration adding another shiny layer of nacre to that tiny seed of memory.

Focus too much on critical interpretation, and you’ll lose the plot. Your Marxist interpretations of the hidden Maoist economic agenda behind “Garfield” shouldn’t cause you to forget that it’s about a fat cat who likes lasagna (even if that lasagna symbolizes the Sacco and Vanzetti case and its impact on Roaring 20s attitudes towards socialism).

Live in the moment without self-examination, and you’ll lurch from event to event without a connecting thread or larger narrative.

We began by considering whether life is pain punctuated by joy, or joy punctuated by pain. Perhaps the answer is that it could be either…and that our lives consist of the process of writing that narrative for ourselves.

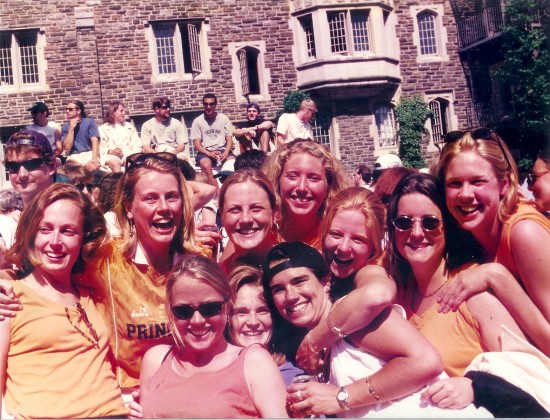

I showed up at Princeton anxious, nervous, and, I realize now, quite wounded from two very difficult years at boarding school. I was incredibly fortunate to find, amid those Gothic towers, magnolia leaves, and foamy keg beer, at last, a place that felt like home … I found a group of women who embraced me. I still felt insecure, and wondered why any of you would want to be my friend. I still wonder that. I look at this extraordinary group of women and cannot imagine why any of you, spectacular as you are, would want to be my friend.

I showed up at Princeton anxious, nervous, and, I realize now, quite wounded from two very difficult years at boarding school. I was incredibly fortunate to find, amid those Gothic towers, magnolia leaves, and foamy keg beer, at last, a place that felt like home … I found a group of women who embraced me. I still felt insecure, and wondered why any of you would want to be my friend. I still wonder that. I look at this extraordinary group of women and cannot imagine why any of you, spectacular as you are, would want to be my friend.

The first photo is from Easter. I’m with my daughter and my goddaughter, and this photograph reminds me of the tight community my family is fortunate to be nestled within.

The first photo is from Easter. I’m with my daughter and my goddaughter, and this photograph reminds me of the tight community my family is fortunate to be nestled within.  The second photo is one that Grace took of me one evening in

The second photo is one that Grace took of me one evening in  The third photo is from the

The third photo is from the  How do I love you two? Let me count the ways.

How do I love you two? Let me count the ways.