Recently I went back to my high school 20th reunion. And, again, I experienced that collapse of time, where years fold in on themselves and and a lifetime and a minute twist together in an disorienting spiral of memory and emotion. It’s not a secret that I wasn’t particularly happy while I was at boarding school, but it’s also true that with every year that passes I respect my alma mater more. I respect it for giving children credit, for holding them to an incredibly high standard, for asking a lot of young people because it knows that they are able to deliver it.

My memories of my time there are few, but vivid. They revolve around cold, dark mornings and nights, running in the snowy woods, wet hair at late afternoon classes frozen into icicles, hours upon hours of homework, the senior play, and oval mahogany Harkness tables.

It was wonderful to be back. Perhaps because my time on campus was not marked by particularly strong social bonds, returning is mostly devoid of the anxiety that revisiting this time in life holds for many. There were, absolutely, joyful reunions with friends I hadn’t seen in a long time. And happy conversations with people I didn’t know on campus but have come to since. Perhaps most of all, it was powerful to watch my children with the children of my friends, all so much closer than we are to the age we were when we met, a fact that is dizzying, unbelievable, and irrefutable in equal measure.

There were a couple of places I was disappointed not to be able to get into, like Phillips Chapel and the indoors of the English classroom building, so I missed seeing them. But otherwise, the day was jammed with special moments.

For instance, my daughter standing in front of the building where my love for words caught fire. Those first two windows to the right of the front steps were where my favorite teacher taught. It was in Mr. Valhouli’s classroom, and in the light of his kind, probing pedagogy that I first sensed my passion for reading and writing throb inside of me. My daughter standing in the intersection of the quad across which I ran, holding my acceptance letter from Princeton (the first line of which said only, in bold all-caps, “YES!”) to hug my dear friend who was also going to Princeton. The friend who is now Whit’s godmother, a true friend of my heart.

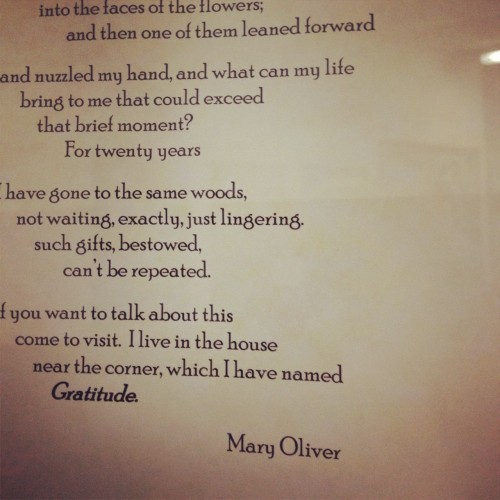

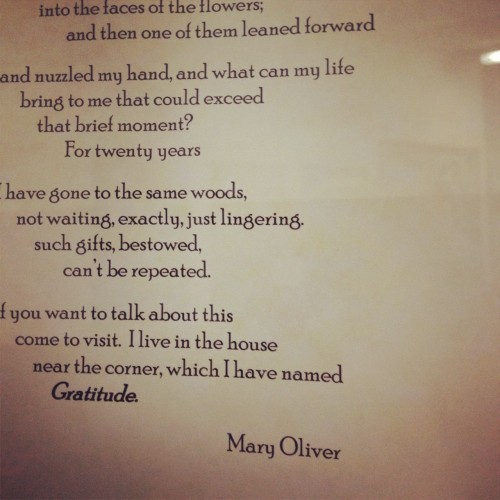

The new science center is downright awe-inspiring, and we wandered around it, agape, aghast, awe-struck. The whale skeleton hanging from the ceiling, the large, professional-looking labs filled with shiny equipment, the walls filled with photographs, equations, and samples of bridge-building projects all drew Grace and Whit’s attention. Mine was captured by this piece of paper, a photocopy of one of Mary Oliver’s poems, stuck on the wall of a Physics lab. That right there tells you a lot about my high school. And a lot about why I respect it so. There’s a place for poetry even inside the world of Physics. This is how I grew up, and it remains how I see the world.

The Academy Building in full sunshine, against a cornflower blue sky, reminds me most of all of my graduation day from this place. It was a hot, early June day in 1992, and all four of my grandparents, my two parents, my sister, and my two godmothers were all there. I am bewildered now to fathom the depth of this showing of support, and while I know I basked in love and family, I wish I could return there to look each of those people in the eye (three of them now gone) and tell them how much I love them, how often I thought of their counsel, how much I valued the ways they had shaped me as I grew into a young adult.

It has been 20 years since that day. It feels like these 20 years flew by in a heartbeat, but I know that each year was lived thoroughly, to its depth and its width. As I grow into my middle-aged skin, inhabiting these years at the top of the ferris wheel, these years in the early afternoon of life, I reflect with nostalgia on a time when I was so young, so mutable, so filled with both promise and sorrow. I feel deep compassion for my long-haired, confused, emotional adolescent self. With the perspective of years, it is simple to identify those two years in New Hampshire as the ones where I learned how to learn, where my intellectual self took flight, where my passion for all the central cerebral interests of my life began. And it is impossible to convey my gratitude for that gift.