Most mornings, I walk Grace and Whit into their respective school buildings. Occasionally, if I have to make it to an early meeting or something, I do “live drop off” instead, letting them hop out of the car while I idle at the curb. For some reason this always brings tears to my eyes. There’s something about their backpacks bobbing away from me, their independence, their resolve, their enthusiasm for school – all of it mixes up into a cocktail that brings tears to my eyes as surely as onions on the chopping board or Circle Game on the radio.

The other morning was no different. I drove away, blinking back my tears, and suddenly I thought: these are the years they will remember as their childhood. We had driven to school all belting out Edge of Glory together, and then we had sat in the car near school singing along until the song ended. I looked in the rear view mirror to catch them grinning at each other, overwhelmed again with the realization that tiny things can bring sheer joy for them.

I remember when Grace turned four thinking: okay, this really matters now. That is because my own memories of childhood begin when I am about four. I actually don’t have that many memories of my childhood, and those I do exist in a slippery kind of way: am I remembering the actual event, or the picture I’ve seen so many times of the event? I wonder if part of why I write things down so insistently now is to address this very fact, this inability to remember when I so desperately wish I could.

My flashes of memory, as limited as they are, begin in the second apartment we lived in in Paris. I was four-ish. So, my assumption was that Grace and Whit would start remembering things from the same general time period. Certainly, they will remember these days. The power of the most mundane moments and experiences – something I’ve long believed fiercely in – was probably particularly on my mind after reading The Long Goodbye last week. For sure, O’Rourke’s memoir had me thinking particularly of the memories of our mothers that endure.

And so I drove into Boston, my eyes still blurry with tears, watching the outrageously beautiful trees that line the Charles, the river that throbs through the heart of my home, wondering what it is that Grace and Whit will remember of these days. We are “deep in the happy hours,” as Glenda Burgess put it in her stunning memoir The Geography of Love, and one thing I’m certain of is that it will be the small moments that most sturdily abide. Will they remember the notice things walks, the trips to the tower at Mount Auburn, trapeze school, and chocolate cake for breakfast? Will they remember the hundreds of nights that I read to them, tucked them in, administered the sweet dreams head rub, did the ghostie dance, turned on their familiar lullabies? Will they remember Christmas, and Easter, and Thanksgiving, and their birthdays?

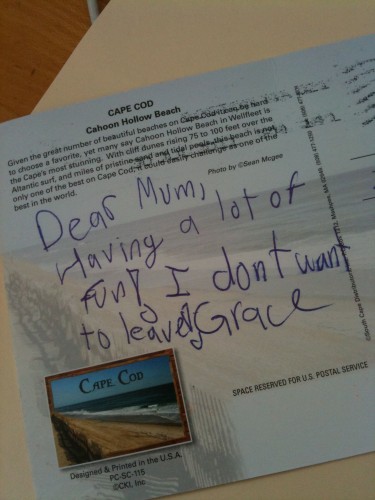

I have no idea what specific events and experiences will be the ones that rise up for my children, out of the dust of the years, some surprising, some familiar. I could easily drive myself insane trying to make sure every single day is stuffed with memories. But I choose not to do that, because, as I’ve written before, the memories that I come back to, rubbing them over in my mind like a hand worrying a smooth stone in my pocket, are almost all from days and moments that were utterly unremarkable, unmemorable, as I lived them. I assume this will also be true for Grace and Whit. So I suppose all I can do is try to be here, paying attention, to the vast expanse of ordinary days we swim in. And to remember, every single day, what an immense privilege each one is.

September 2004, Grace’s first day at nursery school

September 2004, Grace’s first day at nursery school September 2007, Whit’s first day at nursery school

September 2007, Whit’s first day at nursery school