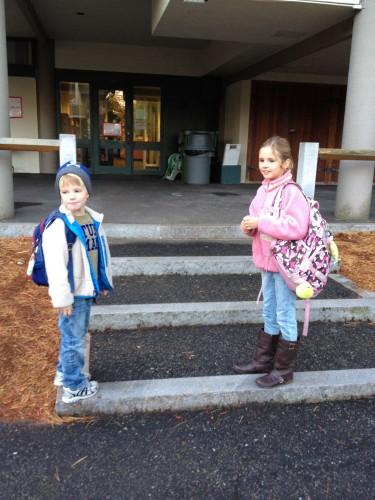

This is my every morning. I park the car, we walk into school, first to Whit’s building, and then to Grace’s. I always trail them up these steps, for some reason, watching their bodies skipping towards the door. Lately I’ve had the physicality of motherhood (and childhood) on my mind, and it is never more apparent than those moments when I watch their ever-lengthening bodies walking away from me.

This is my every morning. I park the car, we walk into school, first to Whit’s building, and then to Grace’s. I always trail them up these steps, for some reason, watching their bodies skipping towards the door. Lately I’ve had the physicality of motherhood (and childhood) on my mind, and it is never more apparent than those moments when I watch their ever-lengthening bodies walking away from me.

We’ve been listening to Love Came Down at Christmas in the car, which Whit loves because it’s “the song he was the drum for.” Last week, one morning, we had a very detailed conversation about my pregnancies with each of them. Whit knows he kicked every time that carol came on and Grace, with her razor-sharp focus on fairness, wanted to know what song made her kick. I don’t know, I told her honestly. I went on to tell her about a day I’ll never forget, at my friend Schuyler’s wedding, in the summer of 2002, when I hadn’t felt Grace (then known as Finbar, gender unknown) for a while and sat on a couch prodding my stomach, my entire world narrowing for the first time to a beam of frantic concern about my child. Okay, she said, satisfied that there was also a story about her inside my belly.

I watch them walk away and I think about all those days when I felt their little feet in my ribcage, when I watched an arm, a knee, an elbow, turn over inside me, a knobby piece of a yet-unknown person bulging against my domed skin as it did so. Just as everyone cautioned, it’s hard to remember exactly what that felt, having a new life swimming inside of me. While I know it was both miraculous and uncomfortable, I wish I remembered more precise details.

The intense physical union of pregnancy gives way, in a moment as brilliant and searing as lightning, to a time of continued bodily intertwined-ness. I miss those days, too, in an odd, grateful, relieved kind of way. And then, as the years of childhood unfurl, gradual but indeniable physical separation occurs. I know there will be a day when my children don’t want me to curl up in bed with them. A day when they will close the doors of their rooms and retreat to a world where I am not welcome. A day when Whit’s first request, upon stubbing a toe, is no longer “will you kiss it, Mummy?”

I fear and dread that day, but I ought not let that keep me from imagining what is right now. Isn’t this one of the central themes of my life? The way I sometimes let fear of what is coming occlude the brightness of the moment? Instead of falling into this familiar groove, allowing myself to be engulfed by an anticipated loss, may I instead lean into what is true right now. Last night I tucked Grace in and discovered that she was clutching a tank top of mine; I hadn’t put her to bed, and in my absence she had gone into my closet and pulled out a piece of my clothing to hold close. Whit still lets me wash his hair and soap his back in the bathtub, and each time I admit I wonder if this is the last time. How long will the simple fact of my physical presence be enough to soothe whatever it is that upsets my children?

I want to stop that wondering and abandon myself to what is. It’s so hard for me to do this. But as I watch Grace’s feet grow and grow, edging into territory where our flip-flops could be confused for each other’s, and as Whit’s teeth fall out, I feel a vague panic about the future encroaching on the present. I suspect part of this is my own deep longing for a day when concerns and anxieties could be so easily solved, in the body of a parent, in a kiss, in a sweet-dreams-head-rub. The solution to this panic, I know, is the most counter-intuitive thing for me: I ought to turn away from it and curl into right now. All I can do is try.