I’ve mentioned my father before, the physicist–poet whose influence looms large over me (as does my mother’s). Well, in a single gesture this week, Dad reminded me yet again of the craggy peaks of his intellect; he read my post about light and responded with an email in which he shared a passage from Paradise Lost. A passage about light. A passage I haven’t read in years, a passage that brought to mind long, drawn-out conversations about ancient poetry under magnolia trees at Princeton, a passage that reminded me that Dad has read and re-read Paradise Lost, the whole thing, on his own, more than once. The guy who has a PhD in Engineering.

You get my point.

Anyway. I wanted to acknowledge my super-cool Dad, for this generous gesture that tells you a lot about the terroir in which I grew up. But I also wanted to share a few of Milton’s truly incandescent lines (a word Dad used in his email, one that is one of my very favorite words, reminding me yet again of the continued power of light in my life). The lines I love best from the (longer) passage that Dad sent me are these:

So much the rather though, celestial Light,

Shine inward, and the mind through all her powers

Irradiate; there plant eyes, all mist from thence

Purge and disperse, that I may see and tell

Of things invisible to mortal sight.

Of course celestial Light, and angels, and the power of faith, religion, and belief are all front of mind right now. But these lines also remind me of some I recently re-encountered, when Grace read them for the first time. She actually told me, that night, as I was tucking her in, that she’d read something she really liked. And she’d thumbed her paperback carefully, found the page, and read me this sentence. And I blinked back tears.

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; What is essential is invisible to the eye.

– Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

I’ve never been afraid to draw parallels between disparate sources (Dr. Seuss and Mark Doty, anyone?), but this one doesn’t actually feel that disparate. And what these two passages remind me of is that light, as a concept, as a trope, as a way of understanding the world, functions both externally and internally. As I continue to strive for lightness – humor and laughter – and to sink into the gorgeousness of the shadows and light and dark at play in the sky, I want to also remember the immense importance of that internal light.

I want to honor the spirit’s seeing, which happens by the beam of that internal light.

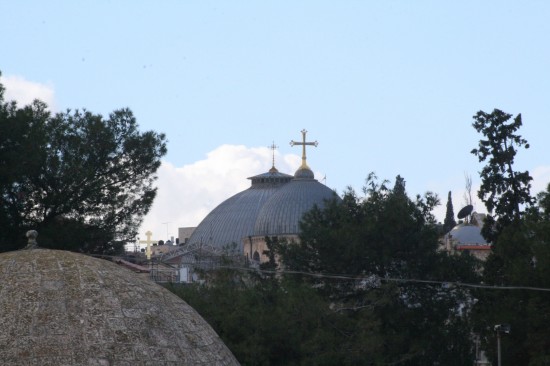

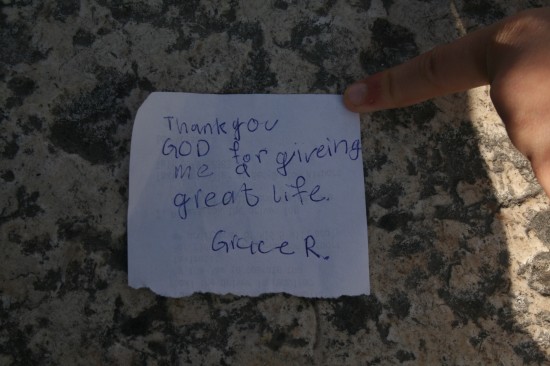

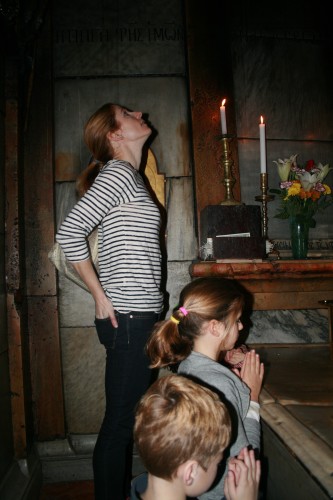

I have been thinking, for days now, of how to describe our magical adventure, our family trip to Jerusalem, a week full of delights and overwhelm and memories none of the four of us will ever forget. We experienced things, individually and collectively, that moved us all deeply.

I have been thinking, for days now, of how to describe our magical adventure, our family trip to Jerusalem, a week full of delights and overwhelm and memories none of the four of us will ever forget. We experienced things, individually and collectively, that moved us all deeply.