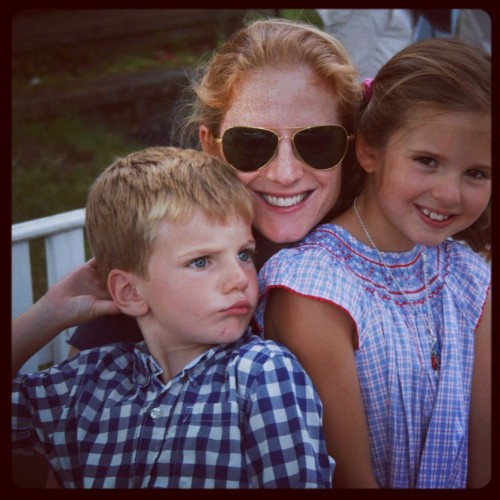

This is within the first hour of Grace’s life. I am bewildered.

That my article on The Huffington Post, 10 Things I Want my 10 Year Old Daughter to Know, resonated with readers was immensely, heart-fillingly gratifying. I am hugely honored and deeply humbled. I was buoyed all last week and weekend by the knowledge that my words – the deepest wishes of my mother heart, at this particular point in my daughter’s life – had burrowed into the thoughts and feelings of even perfect strangers.

And the comments on the piece blew me away. I realized there are things in that piece I passionately wish I’d said differently. Many of the comments were kind, and I cried as I read them, sad for the people who said they wished they’d had parents who had spoken to them like this and deeply touched by people who told me I was a good mother.

See, the thing is, I was never really thought of myself as a mother. Early on in our childhood, my sister and I took on roles within our family. I’m not sure exactly how this “taking on’ occurred, because I am certain it was subconscious on the part of all involved. But as stories and beliefs about a child sink into family lore they likewise seem to saturate our very cells. I was not particularly maternal, it seemed. I never babysat. I wasn’t very interested in dolls. I had literally never changed a diaper until I changed Grace’s. The fact that I adored being a camp counselor belies the assertion that I wasn’t especially interested in children, though it’s true my charges were teenagers and not in fact that much younger than I was.

An endocrine specialist told me when I was 23 that I would never get pregnant without significant intervention. I remember that last experience vividly: I walked away from the appointment feeling grateful to finally understand what was going on with my body, but also with a chilling sense of an emotional instinct being confirmed by my physical body. I wasn’t focused on being a mother, and now it seemed that my body didn’t know if it ever wanted to be one anyway.

And then I got into business school and at age 24 threw myself headlong over the cliff towards the world of Career. It’s not that I didn’t want kids, not at all. I did always assume I would have children, but truthfully I never thought very much about it. I never defined myself through the future children I would have, never planned for that life.

And then.

Those 2 lines on February 15, 2002 changed everything. They blew a hole through that endocrinologist’s certainty that I’d never get pregnant on my own, for one thing. But they also indicated that I’d stumbled onto a new path, one that would meander through dark cul de sacs and swamps before eventually coming out into a light so bright and vivid I still find myself blinking into it, like Plato coming out of his cave.

My embrace of motherhood was not immediate. Oh, no. In fact my put-aside memoir was mostly about that, about the slow and treacherous passage from the moment I delivered my daughter myself to falling in love with her as I’d been told I would.

And yet here I am, a mother almost 10 years, and it is absolutely, undeniably true that this is the central role of my life. (I feel the need to acknowledge that I am both aware of and grateful for my good fortune in conceiving and bearing healthy children). I have been changed in countless, indelible ways by becoming a mother. One essential one is not a change so much as a return, to the page, to writing, to something I had forgotten I needed. My subject chose me, I recently observed, and while that subject is not specifically “motherhood” it certainly arrived on the backs of my blue- and brown-eyed children, announced itself slowly but insistently as their lives unfurled with dizzying speed in front of me.

The truth is that I feel like a fraud, sometimes, like I’m not a “natural” mother, both because my entry into this role was so fraught and because for so long I was not one of those women whose whole self was oriented towards eventual motherhood. I suspect this is why the supportive Huffington Post comments meant so hugely much to me, because there I still contain a reservoir of insecurity about my mothering, my motherhood. I actually believe that many mothers share this deep rooted uncertainty and anxiety, for a host of reasons not necessarily the same as mine.

I have written before, and continue to believe, that most of our suffering in this life comes from our attachment to the way we thought it was going to be. My experience growing into the role of mother, an identity I hadn’t thought much about that has nevertheless come to define my sense of myself, shows me that letting go of those attachments can both relieve suffering and show us great, unexpected joy. Let’s keep letting go of how we thought it was going to be. Who knows what startling joys and surprises lie ahead.

This is the 15th

This is the 15th