“Let’s be in awe

which doesn’t mean

anything but the courage

to gape like fish at the surface

breaking around our mouths

as we meet the air.”

– Mark Nepo

“Let’s be in awe

which doesn’t mean

anything but the courage

to gape like fish at the surface

breaking around our mouths

as we meet the air.”

– Mark Nepo

For the most sensitive among us the noise can be too much.

– Jim Carrey, to Philip Seymour Hoffman

I have not been able to get Jim Carrey’s tweet on the occasion of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s sudden death out of my head. That line has been running through my thoughts pretty much constantly since Sunday.

No. I am no Philip Seymour Hoffman, that’s not what I am saying. And I am not saying I know anything about his private demons or struggles. But I do know what Jim Carrey’s talking about, and I’ve written about it before. The loneliness that is curled at the core of my human experience. The quiet, jagged seed of desolation and sorrow that is buried deep inside of me. The emptiness that I wrote to Grace about, warning her of the behaviors that so many people indulge in to fill the echoing void.

I’m convinced that this gnawing loneliness is a universal aspect of being human, but I’m equally certain that people are aware of it to varying degrees. And there are many ways that people try to distract themselves from feeling it, and some of these behaviors are more socially acceptable than others. Some of them are also riskier, as Seymour Hoffman’s story vividly demonstrates. It’s the socially acceptable avoidance tactics that have always been my personal favorites. This can, and does, lead into a trap: almost exactly two years ago I wrote about the dangerous complexity that is born when the ways you hide from your own life are applauded by the world.

I’m learning to stop avoiding my own life by focusing on external achievement, and beginning to let authentic goals replace brass rings. There is no question I’m making progress. But the thing is, as I get quieter and more in touch with the whisper of my own voice, somehow, the world gets noisier. Maybe that’s what happens, as paradoxical as it is: we shut out the noises, the coping techniques that blur the pain, and in so doing we expose ourselves to the real noise. Does that make sense?

The world’s noise has always affected me in a deep way. It’s not the first time I’ve noted it, and it won’t be the last: I’m extremely porous, and the world seeps through my membranes quickly, powerfully, and, often, overwhelmingly. In the simplest terms I like silence. I was a cross-country runner in high school: is there a sport more designed for someone who likes to be alone, likes to be outside, likes to admire the seasons as they ripple across nature? I don’t think so.

And yet the silence holds so much music. It’s the same way that I now see how the darkness is full of stars almost blinding in their brilliance.

As I turn towards quiet, tune into my own internal world (the hidden geode lined with glittering that Catherine Newman describes), I am by turns dazzled by the symphony of sounds and disoriented by their startling cacophony. You can’t have one without the other, I don’t think. This is a line that each of us walks alone and we all make choices about how to cope with how open and exposed to the world’s noise we naturally are. I am deeply saddened by Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death. Since Sunday I’ve felt a bone-deep reminder that the world’s noise can be destabilizing and terrifying for some, and that we all need to find a way to manage our porosity to the world.

I am a big Kelly Corrigan fan. Her video, with its tag line we won’t come back here, brings tears to my eyes every time I watch it. I loved The Middle Place. I have forced many friends to listen to me read her essay about turning 40, and her sustaining female friendships, which makes me weep. One review I read of her work called her the “poet laureate of ordinary life.” We have the same birthday. I mean … I adore her.

All of this means that I dove into her new book, Glitter and Glue: A Memoir, enthusiastically. My interest in, curiosity about, and affection for the mother-daughter relationship is extremely well documented here. I was intrigued to read Kelly’s thoughts on her mother, who figures quite peripherally in The Middle Place.

The book’s title comes from something Kelly’s mother told her when she was a child: “Your father’s the glitter but I’m the glue.” That single line brought tears to my eyes because it reminded me of my own childhood: I’m the child of a glittering mother, who’s been seeking that same kind of dazzle in her friendships for many years. Myself? More glue, I think.

Kelly’s mother was and is formidable, her rules strict, her love tough, and her authority absolute. Glitter and Glue starts out with the assertion, so familiar to all daughters, that we only understand our mother’s influence – and brilliance, and love – once we are out of their shadow, and with time. Most of Glitter and Glue takes place in a family’s home in Australia, because it is there, shortly after her college graduation, that Kelly begins to see her own mother with clarity and affection. After taking off on a big adventure to see the world, Kelly and her friend run out of money. They need jobs, and the only ones they can find are as nannies. Kelly moves into the Tanner house to help shortly after their mother (and wife) has died. The Tanners are the central characters of the book: Martin and Milly, the children, Evan, the step-brother, Pop, the grandfather, and John the grieving father and recent widower.

During her five months with the Tanners, Kelly develops relationships with each member of the family. She also hears her mother’s voice all the time – as do we, the reader, in the form of italicized phrases. “God knows, every day I spend with the Tanners, I feel like I’m opening a tiny flap on one of those advent calendars we used to hang in the kitchen ever December 1, except of revealing Mary and Joseph and baby Jesus, it’s my mother,” Kelly reflects on the unexpected but undeniable way her mother is animate in this foreign house halfway around the world. Kelly had left home, certain that the grand experiences she sought could not be had at home, but her time with the Tanners teaches her that important, formative things can happen inside the mundane-looking reality of family life. Towards the end of her time in Australia she reflects that “…I was wrong, things definitely happen in a house – big, hard, beautiful things.”

There are two ways that Kelly’s time with the Tanners brings her mother to mind. More obviously, she is being the mother, as the only adult female in the family. But, less visibly but equally importantly, she is keenly aware of the contrast between Martin and Milly’s lack of a mother and her own strong one. In both these ways, Kelly’s mother looms large over the time at the Tanners’. Her voice guides Kelly as she takes on a maternal role for the first time. Simultaneously, as Kelly realizes how interwoven her mother is with her own identity, she keeps tripping over all the painful ways that this won’t be true for Milly and Martin.

It’s not until after I put her to bed that night that I can bring myself to think about my mother and the reams of things she did for me that could and should have softened me. What is it about a living mother that makes her so hard to see, to feel, to want, to love, to like? What a colossal waste that we can only fully appreciate certain riches – clean clothes, hot showers, good health, mothers – in their absence.

This blend of omniscence and invisibility defines Kelly’s dawning awareness of her mother’s importance. This observation is so accurate it made me almost uncomfortable: what did I take for granted about my mother – what do I still take for granted? It made me want to pick up the phone and call the mother I’m so privileged is still alive, well, and nearby, and say: thank you. At one point, Kelly chastises Milly with words that ring in her head, even as she says them, as “verbatim Mary Corrigan.” This, I imagine, is a fairly universal experience: hearing our own parents’ voices as we say things to our children that we recall (and probably disliked) hearing when we ourselves were small. For me, right now, the main one is “only boring people are bored.”

The narrative moves smoothly back and forth between describing Kelly’s life at the Tanners and recollections of her own childhood. The memories of growing up illuminate Kelly’s mother beautifully, and I had a powerful sense of her as a wise, smart, practical woman who did not budge after she made up her mind and cared more about doing the right thing by her family than she did about their liking her. As Kelly says goodbye to the Tanner family at the airport, she finds herself overcome with emotion. Her powerful reaction surprises her, and as she reflects on all the details about their lives she will remember, she also realizes part of its root: Martin and Milly taught her a lot about her own mother.

I’ll know it was the Tanner kids who pointed me back toward my own mother, hungry to understand her in a way I clearly didn’t yet. They put her voice in my head. They changed her from a prosaic given to something not everyone has…

One strand of the book that I found tremendously compelling was Kelly’s clear and incisive ability to understand her parents’ marriage, and the different – but equally crucial – roles each had played in the family. As she becomes a mother herself, Kelly begins to see the ways in which being the “glue” to her husband’s “glitter” were a choice, and not always an easy one. A new identification with her mother develops when Kelly has her own children: “I began the transition from my father’s breezy relationship with the world to my mother’s determined navigation of it.”

Glitter and Glue is told in Kelly’s inimitable, funny, wise voice, the one that is now familiar from her other work and which feels like I’m talking to a particularly well-spoken and hilarious friend. Over and over again I laughed and blinked away tears, often on the same page. On the last page of the book Kelly says, “I want to tell my mom that I admire her, the quiet hero of 168 Wooded Lane,” and the whole story comes into sharp, bright focus. This book is a love letter to her mother, just as The Middle Place was one to her father. Even though the child and adolescent Kelly couldn’t necessarily appreciate her mother in the moment (and isn’t this true for a great many of us?) , the middle-aged one can recognize the ways in which Mary Corrigan contained “the strongest currency [a child] would ever know: maternal love.”

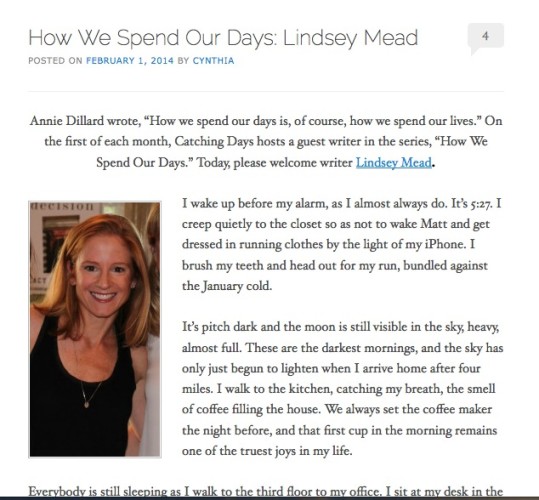

It is such an immense honor to be profiled on Cynthia Newberry Martin’s blog, Catching Days. She runs a wonderful series, called How We Spend Our Days, which features a writer each month talking about, literally, what they do during the day. It is quite literally a dream come true to read Cynthia’s extraordinarily generous words introducing me.

And today my piece, about a typical January day, went live. I hope you will read not only this short essay, but also poke around Cynthia’s blog. Other writers in her series include Dani Shapiro, Pam Houston, Cheryl Strayed, Jane Smiley, and Anne Hood. Did I not mention: a dream come true?

Thank you so much, Cynthia, for this enormous honor.