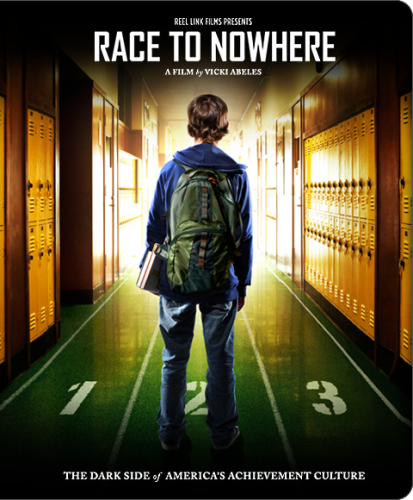

I have been thinking a lot about The Race to Nowhere, and what I wrote about it, and about the thoughtful comments that people made. My sister, the younger-and-wiser Hilary, and I have been going back and forth in email about it too. She is the only person on the planet who shared with me the overwhelmingly rich and challenging terroir of our childhood and uniquely qualified to discuss those days and to hold up a mirror to me. She is also a deeply thoughtful person and an educator, so I am particularly interested in her view on this subject.

And she said something that really struck me. With regard to The Race to Nowhere, she averred that she did not like the way that “achievement has become anathema.” And I agree. Fully. In fact when I read the comments on my post last week, I found myself with an uneasy feeling in my stomach, that creeping sensation of not having adequately or articulately conveyed what I really feel. I’m worried I left out a big piece of my view.

And so here I will try again. I think achievement is terrific. I have written time and time again of how important it is for a child to feel the feel mastery. Of a skill, a place, of themselves. I will never forget the glow in Grace’s eyes when she rode a two-wheeler alone, the light in Whit’s face when he swam a lap of the pool solo, the sheer, palpable delight Grace felt when she began reading chapter books. These accomplishments are immensely self-esteem building, and I would never, ever suggest that they are a bad thing.

In my life this theme reached a crescendo at Phillips Exeter Academy, where I went for 11th and 12th grade. Frankly, my years there were relatively unhappy, for a constellation of personal reasons. Despite this, even while I was there I felt a deep respect, almost a reverence, for the place, an awareness that I was somewhere unique. The further I get from Exeter the more crystalline my appreciation of the place becomes. As the years have passed, and since I’ve had my own children, I’ve come to understand why.

It feels rare, these days, that an institution that deals with children says as baldly as Exeter does: we have high standards. And we know you can meet them. I’m not entirely sure why that’s a threatened stance in education today, but as far as I can see it is. And Exeter unflinchingly does that. I’ve never been somewhere that so fiercely believed in the potential of its students: we won’t lower the standards, the voices seem to whisper, because we know you can do it.

And they do. It’s powerful, being believed in.

Nowhere I’ve been to school before or since has even remotely touched the education I received at Exeter. Exeter pushed me and defied me and never, once, for a single second, gave up on me. And you know what? I could do it. It is the first place that I began to believe that I might have something to say.

I think the problems begin when one’s identity becomes entirely intertwined with achievement. This is what happened to me; I entirely lost the voice of my soul, which was a whisper, because the voice of the world telling me what to do, and applauding me when I did it, was so deafening. Of course the risk of this is high when you begin achieving, because the world’s adulation feels good. At least if you are a pleaser like myself.

But never let me miscommunicate my lack of commitment to the idea of excellence in general, and of achievement in specific. I hope to raise children who are tuned in enough to their inner voices to discover what it is that makes their hearts soar, and full of energy and passion enough to go after those goals with everything they have.