I love the New York Times By the Book column, which appears in the Sunday Book Review. A friend and fellow passionate reader recently shared one with me with the note that it would be awfully hard to answer the questions. Then I thought: this would be fun to try. The questions vary slightly week to week, but the gist is the same. I’d love to hear your responses to these questions, too, if you are so moved!

What books are currently on your night stand?

Final Jeopardy by Linda Fairstein (I am in a difficult work period, and not much reading is happening)

The Givenness of Things by Marilynne Robinson (these essays by possibly my favorite writer are dense, beautiful, and too smart for me; I’m dipping in and out)

The Book of Awakening by Mark Nepo (permanently on my bedside table)

What’s the last great book you read?

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi (I wrote about it here)

What genres do you especially enjoy reading? And which do you avoid?

I love memoir, poetry, and some fiction. I almost never read historical fiction (which is part of why I was somewhat resistant to All the Light We Cannot See – which I eventually adored).

What’s the last book that made you laugh?

Yes Please by Amy Poehler.

What’s the last book that made you cry?

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi.

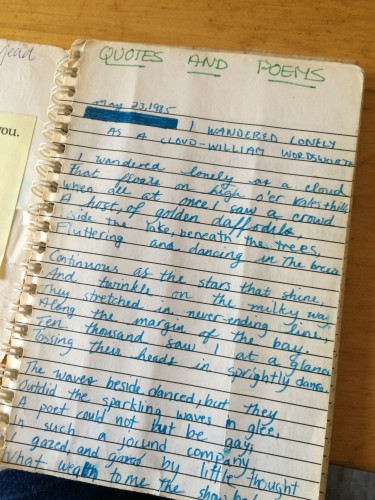

What’s your favorite poem?

The Real Work by Wendell Berry.

Who is your favorite fictional hero or heroine? Your favorite antihero or villain?

Hero/heroine: Albus Dumbledore and Harry Potter (Harry Potter), Lyra Belaqua (His Dark Materials Trilogy), Eve (Paradise Lost

), Charity Lang (Crossing to Safety

).

Villain is harder. Nobody comes to mind.

What kind of reader were you as a child? What authors and books stick most in your mind?

I was an avid reader, devouring lots of books of all kinds of genres. I remember loving the pantheon of great female heroines in that stage of books: Meg Murry in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, Harriet in Louise FitzHugh’s Harriet the Spy, Karana in Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins

.

I also loved Bridge to Terabithia. I am absolutely certain that I would have been a passionate fan of Harry Potter and his world if it had existed when I was a child.

If you had to name one book that made you who you are today, what would it be?

This is very hard to answer, but I think I would cite the work of the three poets on whom I wrote my senior thesis in college: Adrienne Rich, Anne Sexton, and Maxine Kumin. That year was the first time I dove into what would become a central theme of my life, the intersection of motherhood and creativity and the ways in which they both enrich and detract from each other.

What author living or dead would you most like to meet, and what would you like to know?

I wish I had known Oliver Sacks and Paul Kalanithi, and I would love to meet Atul Gawande and Abraham Verghese. I am fascinated by the doctor-writers, and by both spheres in which they live their lives (and, as many people know, I wish I was a doctor).

Disappointing, overrated, just not good: What book did you feel you were supposed to like, and didn’t? Do you remember the last book you put down without finishing?

I’m ashamed to admit this, but I just could not get into Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend. I really wanted to. I really tried. So many people whose book recommendations to me are infallible suggested I read it. It simply did not hook me. I’m sorry!

Whom would you want to write your life story?

Katrina Kenison. Nobody shows the way ordinary life shimmers with meaning the way she does.

What do you plan to read next?

My Name Is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout and Why We Write About Ourselves: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature

by Meredith Maran.

I’d love to hear your answers to these!