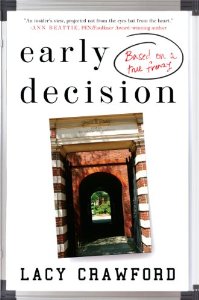

I have known Lacy Crawford a long, long time. We met our freshman year in college and both, I think, recognized a kindred spirit. We shared long walks on our campus’s tow path, an awareness of how the texture of light changes throughout a day and throughout a year, a deep respect for the solstice, and long red hair. We also both loved words: poems, essays, novels, lyrics, quotes. Since 1992 Lacy and I have been trading book suggestions and passages we have read that moved us. She is without question one of my most valued and cherished friends, a true native speaker, and someone I’m grateful to have in my life every single day.

Reading Lacy’s first novel, Early Decision, was an extraordinarily wonderful experience. I’ve read many other books by friends but never one by someone I have known so well, so long, or so intimately. Though Lacy created a rich and textured fictional world, I could also hear her voice in certain sentences, and it felt like she was telling me a story over a bottle of wine in my living room. Early Decision is published tomorrow, and I can’t possibly say enough about how much I loved this book.

Early Decision is narrated by Anne, a private college admissions counselor, and follows the college application season of five high school seniors. In the process of working on his or her personal essay, each teenager excavates who they really are and what they truly want. Lacy makes the point that personal essay, and the deep reflection required to execute it well, can lead us to a more profound understanding of ourselves and our experience. Isn’t this what great writing really is? For the writer and, of course for the reader: a gateway to richer knowledge of this life.

Self-discovery and self-determination are central themes of Early Decision. These are echoed in the dedication (always one of my favorite parts of a book) in which Lacy says to her sons: “May your decisions be your own.” Anne is very much engaged in both processes at the outset of the novel. She is a relatable and human character whose own sense of not yet being fully in the world underlines her role as an advisor. She is observing, and consulting, but she feels she is not yet living.

Here is what was going to happen: Anne was going to wake up one morning in full possession of the authority she needed to go out and start her life. To acquire the position she really wanted – whatever that was – and succeed. Like Gregor Samsa in reverse, she’d reach her two feet to the floor and head into the world a whole person.

She did not know how to explain exactly why it hadn’t happened yet. She had been careful and diligent. She’d earned terrific grades….And there she was, at play in the fields of the word, except that the amber reading rooms revealed themselves to be a sort of Neverland, where nothing ever happened, and nothing ever would.

(I have to mention that the offhand Kafka reference is vintage Lacy, and put me back in the mind of a freshman seminar on European Literature in which I read The Metamorphosis for the first time; Lacy wasn’t in the old-fashioned sunlit lecture hall so filled with both ideas and energy with me, but I feel as though she was.)

Many of us, I suspect, can relate to Anne: a character who’s followed the rules her whole life, done well in school, grabbed every brass ring. She chose to pursue a graduate degree in English and it is there that she discovered the unfortunate truth that “so much passion should come to nothing.” She leaves school and becomes an independent college admissions counselor, making good money if not the kind of impact that she longs for.

Anne is haunted by this sense that though “her friends read the currents and hopped on in: school-work-love-life,” she instead “teetered there, paralyzed.” There is both irony and pathos in the way that Anne so ably guides her students to epiphanies and to clearer senses of what they want to do and be while being so utterly stuck herself. Of course, perhaps the dilemma is one of definition: to me it was clear that Anne has hopped in, and that despite her sense that “she had no contribution to make,” she is already making one.

The five students with whom Anne works are all vividly drawn, from Sadie’s angst about her parents’ role in her college choice and facade of confidence that covers a profound loneliness to Hunter’s boat-sized sneakers and deep but parentally-disapproved passion for the American West. They serve, ultimately, as foils for Anne, though, and at the end of the day it is her character who has most stayed with me.

Lacy also makes a point about modern parenthood which is uncomfortable in its accuracy. Most – though not all – of the parents in Early Decision are of the now-familiar helicopter type, hovering over their children, hoping that through sheer effort and good (or so they think) intentions they can protect them from harm and insure their happiness. This approach backfires, and Anne observes that in many ways all the “supports” that privileged parents can provide their children send one message, brutal in its simple devastation: “whatever you can do, it’s not good enough.”

For both parent and child, the college application process is surely among the most fraught moments in the long-but-short season that is parenting. How can an experience so wrought with powerful anxiety, galloping hope, and fundamental identification be simple? Anne stumbles into these weeds more than once, noting for example the “real, tender spot” that is “a mother’s projection onto her only child.” It’s almost impossible to imagine a choice more weighted with importance in today’s culture than college.

“Alexis, where you go to college is not the same as who you are,” Anne tells one student, who replies, “No, but it shapes me. It, like, shapes everything.” And it does. Lacy wades without hesitation into this whitewater of love and loyalty, of expectations and dreams, of privilege and luck, and Early Decision is full of fascinating reflections on what it is that really makes us who we are. And of course the answer is neither as simple nor as complicated as those college admission essay questions.

As Anne helps steer her students to a better understanding of themselves and to the best possible college outcome, she grows too. My only wish is that she was more aware of how important her influence on these teenagers is. She reflects that maybe “college was best thought of as four years in which adolescents might learn to use the pronoun “I” and mean it,” and I couldn’t help thinking that I’d been watching her do the same throughout the novel.

I loved Early Decision and know you will too. I’m lucky enough to have read other things Lacy has written, and they are all beautiful. I know that when Anne says that “quite simply, she loved words most of all,” that’s also Lacy talking. She does, and so do I. In Early Decision Lacy has written an entertaining and topical book with deeply-etched characters and some truly vital messages. There are big risks to the currently-accepted way we parent, there is immense value in thoughtful, engaged reflection, and those who are able to inspire and shape this kind of thinking deserve our real gratitude.

I’m grateful to my friend Lacy for writing this book, for the passionate and enduring love of words that she shares with me, and for being the kind of rare friend who has helped shepherd and midwife some of the most important, and painful, moments in my own self-development.