Before we went to Jerusalem, I had an exchange with my friend Aidan about how mothers universally doubt themselves. This is simply and inherently part of the terrain, she said, and I agree. But for days after our conversation I found myself thinking about those moments – rare, but important – where I have trusted myself as a mother even when the prevailing wisdom said otherwise. To understand how vital these experiences are to me you have to understand that I was never a “maternal” person – I had never changed a diaper until I had Grace, I didn’t babysit as a kid, and having children was never part of the future I ran so aggressively and directly for. It wasn’t not part of the vision I had of my life, but somehow it – motherhood – was never an explicit part of my plan.

And then, as you know if you know me or read this blog, motherhood came upon me suddenly, without warning; my pregnancy, a surprise, announced itself the same day that Matt’s father was diagnosed with a terrible illness. Indeed, Grace’s gestation, birth, and infancy are wound tightly around my father-in-law’s illness and eventual, miraculous heart tranplant.

All of that is to say that I reflect with a very real sense of wonder at the moments when I did trust my own mothering instincts. I was often not aware of this in the moment, but with perspective certain turning points stand up, insistently, reminding me of the undeniable power of an identity to which I’d never given much thought: mother.

During my labor with Grace, I went somewhere I’ve never been again, to a land of incendiary and incandescent pain, and I knew somehow that she and I were going to be okay. A more conventional birth environment probably would not have allowed this to happen, so my choice at 28 weeks to move to the midwifery practice at the small local hospital – which was, on the face of it, somewhat radical – is one I continue to be proud of (and amazed by).

When Grace was almost 2 and she had some symptoms that our doctor could not understand. He sent us to a specialist at Children’s, and she had blood work, x-rays, ultrasounds, a CAT scan. The doctor began talking about possibility of a brain tumor. In this midst of this – a time that I recall more than anything as utterly devoid of panic – I decided to switch her from soy milk to rice milk. I was worried about the estrogen-mimicking qualities of soy. All of her doctors scoffed at me. Her symptoms disappeared in 2 weeks, and I’ve been profoundly skeptical of soy ever since.

When Whit was 3 his nursery school teacher was worried about his speech, and was unsure whether something cognitive was going on. She sent us to speech therapy, where had him evaluated, and the whole time I failed, again, to freak out. I knew he was fine and he was (and is). He just speaks – to this day – with a slightly funny accent. Now it makes us all laugh.

When Grace was 5 (almost 6) she flew on an airplane alone. She flew from Philadelphia to Boston as an unaccompanied minor. I put her on the plane (well, I watched her walk down the gangway with a flight attendant) and Matt and Whit met her at the gate in Boston. Unbeknownst to me, she wrote about it in her kindergarten journal, and I cried when I saw it at our parent-teacher conference. I received stinging criticism on the playground and from other mothers (notably, not from any of my close friends). To this day she talks about the experience, evincing great pride and self-confidence about the fact that she did it.

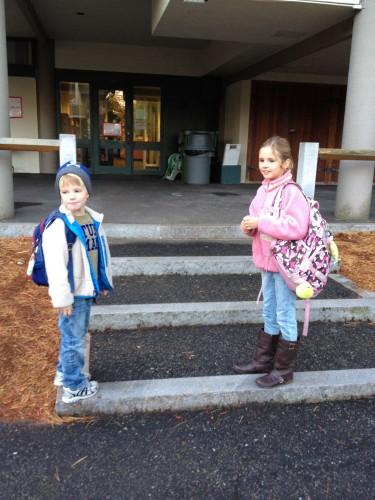

And these days, I follow my intuition every day. It weaves a narrow path, glimmering, through the overscheduled, overstuffed, more-more-more world of childhood today, and I try to follow it, hand-over-hand, like I’m palming a ribbon. I take my children for walks, I take them to the playground, we thrill at the small sparrow on the porch. I worry – I’ll admit it, a lot – that their lack of skills at Mandarin or violin or hockey will be a problem eventually when it comes to applying to schools, colleges, etc. But even more, I believe in the small still voice in my head that says: protect this time.

Aidan, thanks for prompting this conversation, for causing me to dive into my own memories, to remember anew that I do have instincts here, despite how often I bemoan the fact that mothering does not come naturally to me.

Do you have memories like these, about any aspect of your life, that bolster your trust in yourself?

This is

This is