Grace, Beginners. June 2008

Grace, Kindergarten. June 2009

Grace, 1st grade. June 2010

Grace, 2nd grade. June 2011

Grace, 3rd grade. June 2012

Whit, Beginners. June 2010

Whit, Kindergarten. June 2011

Whit, 1st grade. June 2012

Grace, Beginners. June 2008

Grace, Kindergarten. June 2009

Grace, 1st grade. June 2010

Grace, 2nd grade. June 2011

Grace, 3rd grade. June 2012

Whit, Beginners. June 2010

Whit, Kindergarten. June 2011

Whit, 1st grade. June 2012

I separated my shoulder last fall, part of my brief sojourn in and introduction to the foreign and awe-inspiring land that is pain. The injury hurt a lot in the immediate aftermath, and it has mostly but not entirely healed. I’m told that’s part of the deal with separated shoulders: the joint is never quite the same again. On random days, doing motions I do every day I will experience a startling jolt of pain. I can never predict when or why it will come. Also, I have a small but noticeable bump where my collarbone meets my shoulder. Fortunately my collarbone and shoulder are sort of bumpy in general, so it’s not quite as stark as it might be, but it is still noticeable if you look. I have a bump and I always will.

After 6 weeks of recovery, I went back to my orthopedist. I asked him, tentatively, whether the bump would ever go away. He is a tall, gentle man about my age, and he looked directly at me in the small room. I’ll never forget what he said next.

“No, it won’t.” I swallowed. “But you know what? If you’re living, you’re going to get bumps. I have a bump on my shoulder. You’re 37. Don’t we all have bumps? Everybody’s got a bump.”

I laughed it off in the moment, but in retrospect I think there was deep wisdom in this comment. Of course this moment has been on my mind lately as Grace’s collarbone heals. She has a small but visible bump that we are told will flatten out as she grows. It’s on her left side, too, and I find this parallel both totally coincidental and breathtakingly not.

These bumps are just like our scars, outward manifestations of places we’ve been broken and healed. Whit’s long scar on his leg, the trace of a skidding epi-pen, has already faded from angry red to raised white. Grace’s broken bone, originally an enormous protrusion from her collarbone, has begun to flatten out and presumably the bones have begun to knit together. At 7 and 9 my children have already been marked by life. I myself am a map of scars, internal and external: several different bones healed, spots where suspicious moles were removed, the scar where I was hit on the face by a wine press when we lived in France.

We are all marked by our passage through life. Some of these marks are visible and some are not. I think it is valuable to remember the moments and experiences that made marks on us, for better or for worse. They are part of what shaped us into who we are now, after all. This reminds me of a passage from Donald Miller’s lovely book A Million Miles in a Thousand Years

Last year, I read a book about a man named Wilson Bentley, who coined the phrase “No two snowflakes are alike.” He is the one who discovered the actual reality that no two snowflakes are geometrically the same. Bentley was a New England farmer who fell in love with the beauty and individuality of snowflakes…. What amazed Bentley was the realization that each snowflake bore the scars of its journey. He discovered that each crystal is affected by the temperature of the sky, the altitude of the cloud from which it fell, the trajectory the wind took as it fell to earth, and a thousand other factors.

Big thanks to Erin, who told me she likes her own private collarbone bump for the reminder it is of her brave, tough child self. I hope Grace feels the same way someday.

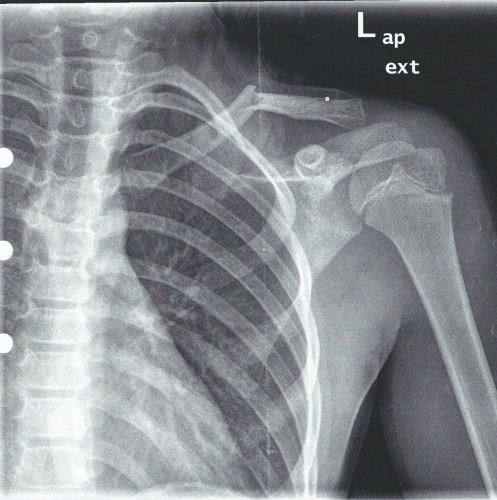

Grace has had several x-rays over the last week or so. The first one in particular haunts me. It shows half of her rib cage, her shoulder socket, and her clavicle, clearly broken in two right in the middle. I have it on CD and on a piece of paper and I keep looking at it, marveling at how a single second can break something in us so dramatically. Looking at it also sends me into the disorienting tunnel of memory, the image of Grace’s ribs colliding in my head with the memory of the only ultrasound I had when pregnant with her. I remember two things about that experience: the first is of my breath catching in my chest when I saw the tiny but bright blinking light on the fuzzy screen, proof positive that another heart beat under my own. The second is of the regular circles that arced through the middle of the oddly shaped blob, the string of pearls that I quickly realized was my baby’s spine.

And here on last week’s x-ray is that same spine, those tiny bright pearls, grown into an actual spine, into the bones of a child only a foot shorter than I am.

There is another reason, though that the cloudy white images on the black background astound me. The bones appear ghostly, bird-like, insubstantial, striated with brighter and fainter white. They remind me immediately and indelibly of the enormous swollen full moon I ran towards the other morning. That moon, hanging on the horizon as the sky broke open into dawn’s Easter egg blues and pinks, was similarly mottled, almost translucent while also undeniably, defiantly present. There is something about the shadowy bones on Grace’s x-ray that reminds me intensely of that moon. They share the quality of being simultaneously indelible and tenuous.

The duality of sturdiness and fragility which I see in the texture of the moon and my daughter’s bones underlies all of life, of course. For me, its most poignant manifestation is in my children. But there is something else, another echo of the moon in my daughter’s very bones. The moon pulls the tides and the bodies of women in fundamental ways, and reassures me on some deep level that I still can’t quite articulate. Both the full moon hanging in the dawn sky and the shadows of my daughter’s bones on a piece of paper took my breath away. What I’m realizing is that that might be because, in some way, they are composed of the same material.

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. – Ernest Hemingway

It seems like the world is composed of those people who break bones and those who do not. I’m the former, and my husband is the latter. At this point Grace seems to fall in my camp. I’ve been thinking a lot in the last week about what it means to be broken, and then to heal. I do realize that not everything in life is a metaphor – sometimes a cold is just a cold, a friend told me once – but this one is hard to avoid.

As scars speak of wounds we have suffered and healed from, so too do our bones bear the marks of our journey, our falls and our recoveries. The big difference, of course, is that bones, when healed, are invisible to the naked eye. That means that my body is full of healed breaks, bones that have reset themselves, grown back together, not as perfect as before, not as straight, but (as of now) solid

I am easily broken. And yet I have always, so far, healed. It’s hard not to ponder why it is that some of us are more breakable than others. Did Grace somehow inherit my predisposition towards breaking? It wouldn’t be the only difficult legacy of mine she’s received. Am I weak? I often feel that way, there’s no question: fragile is one of the words I would use first to describe myself. But as I think about this more it occurs to me that this is perhaps just a physical manifestation of my emotional and spiritual orientation towards the world. Maybe my bones simply echo the way my heart is easily broken, by all the gorgeousness and pain it witnesses every day. Maybe I don’t know any other way to be, deep down in my core, in the very marrow of my self, than vulnerable to breaking.

I understand that there is great pain in breaking, but I also have to believe there is much to learn. At the very least it makes me appreciate being whole. And of course it fills me with awe, the idea that bones, the scaffolding on which our entire bodies hang, can knit themselves back together. The analogy this offers for life itself is compelling to me, and inspiring. I hope that if Grace did inherit my propensity for breaking she also can see the beauty in this way of life.

Have you broken a lot of bones? Do you think that makes a person weak?

Saturday was an absolutely perfect day. Cloudless sky, 75 degrees. I took Whit to soccer and then he and I joined Matt on the sidelines of Grace’s game. She had only been on the field for a few minutes when she took a simply heroic fall. She literally went flying through the air before crumpling to the ground on her left shoulder. There was an audible gasp. And then, worse, she was slow to get up. All the players on the field sank to their knees. I watched her coach approach and ask her if she wanted to keep playing, watched her shake her head, and watched her walk off the field next to him with her head bowed. I purposely didn’t rush over to where she sat with her coaches and team on the other side of the field. I felt like I should stay out of the way.

But at half time, Matt and I went over, and Grace was in quiet tears, holding a tiny bag of ice to her shoulder (one of her teammates had scooped a few ice cubes out of her water bottle and put them into the bag that had held the snack apples, a detail that charmed me). I immediately announced I was going to take her to the ER for x-rays and neither coach fought me. Yes, that makes sense, they nodded. The whole way to the hospital, she cried softly.

After a long wait they finally put us into a room and I helped Grace change into a johnny and lie down on the gurney. “Will you lie with me, Mummy?” she asked plaintively, and I did. I curled my body around hers and rested my chin on top of her gold-streaked brown hair. She whimpered quietly, and I could tell she was in a lot of pain.

“You’ve broken bones too, right, Mummy?” she said suddenly and I smiled in spite of myself. For years and years I’ve maintained that if you haven’t broken any bones you’re “not trying hard enough.” This is an obnoxious thing to say, I realize, and I think mostly I’m trying to explain to myself why I’ve broken one ankle, one arm (both bones, both compound fractures), three ribs, and assorted fingers and toes.

“Yes. I’ve broken a lot of bones. Unfortunately I think getting hurt is part of the deal. It’s going to happen sometimes when you do sports. I’m pretty sure there will be more injuries to come in other games. And in general, in life.” I hesitated. “But I promise,” I blinked back the tears that sprang to my eyes. “I promise you it’s always worth it to play.”

We lay there quietly for a while. Then it was time for x-rays. She was very freaked out by being alone in the dark room, by the lead apron, and by the big machine aimed at her shoulder. By the time we were finished there she was weeping in my arms again.

Then we went back to the room and onto the gurney. It was quiet in the ER on a gorgeous Saturday afternoon, and I could hear our breathing. “Mummy, you know what?” Grace turned her head slowly to look at me. “This is like when I had something in my eye the other day.” (After a protracted effort to get an eyelash out of her eye, she had been in real pain for hours; my guess is that she somehow scratched her eyeball). “You know, I realize how much I’ve been taking for granted all along.”

I tried hard not to cry. I looked right in her mahogany eyes, nodding, biting my lip. I felt the feathers of holiness brush my cheek, the sensation of something sacred descending into the room, as undeniable as it was fleeting. There have been a few moments like this in my life – more than a handful, but fewer than I’d like – when I am conscious of the way divinity weaves its way into our ordinary days. This was one.

That night when I tucked her in her arm was propped on a pillow pet and her eyes were wary. She was very worried about rolling over and injuring herself more in her sleep. I smoothed her hair back from her forehead and kissed her cheek, murmuring again how proud I was of her and how brave she had been.

“Mummy, I just want to say thank you again.” With her good arm, she clutched her teddy bear to her chest as she spoke.

“Why, Grace?”

“Thank you for being there with me all day. For always being with me.” Her eyes brimmed and mine did too. I hugged her because I didn’t have words to express what I wanted to say. Which is that there’s nowhere I want to be but right here with her. That I don’t want to miss a single second of this season of my life, or of hers.