It’s Saturday morning, 6:24. I’ve been up since 5:00. Woke up and just could not go back to sleep. Matt got home very late from a trip and so he’s sleeping. Whit just got up and despite my entreaties that he go back to bed, he’s sitting at his desk, down the hall from mine, working on homework. Grace will probably sleep until we wake her up (see: teenager).

We had the most wonderful dinner with my parents, aunt and uncle, and beloved favorite cousin and her fiance last night. Grace and Whit adore my aunt and uncle, who came to the Galapagos with us, and my cousin and her fiance. It was a lovely, lovely evening and I left feeling replete with love and family. Family was running through my veins, you could say.

We were all up late. I expected that we’d sleep in this morning. Instead, I found myself lying in bed at 5am, wide awake, my head racing through various topics big and small. It occurred to me that this – this behavior, this place of being, this racing mind early in the morning – might be the opposite of ease. It’s ironic that I chose ease as my word of the year when 2016, so far, doesn’t feel like it’s full of ease. Maybe it’s not ironic at all, of course. Maybe it’s precisely right. Maybe some deep part of me knew that this would be a year of transition and in-between-ness, and that I needed to remember the value of ease as I journeyed through it.

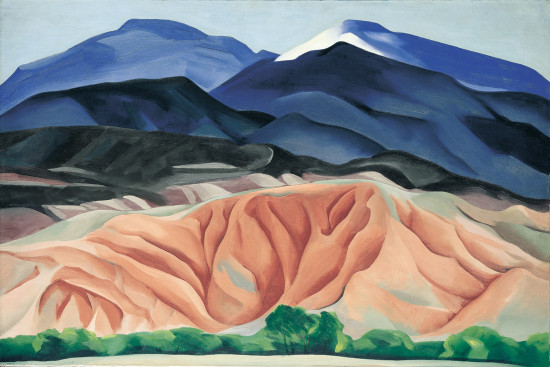

When I think of ease, the words that come to mind are relaxed, calm, comfortable. The only one of those I feel right now is calm. In the midst of right now’s shifting sands, in all the uncertainty that occludes every day, in the fog of the not-knowing that permeates every day, I feel calm. I can feel my breath entering and leaving my chest. I can close my eyes and see certain images – the ocean at my parents’ house south of Boston, the flickering of candles in Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the setting sun from the tower at our nearby cemetery that I love – to which I return, over and over.

Maybe this is ease. This allowing, this honoring, this breathing, this listening. This being here. That’s all I can do, today and, really, every day. I haven’t written much about this year’s word of the year, though I think about it a lot. Maybe it’s taking root in my soul and in my cells in some kind of quiet, slow way. As ease does, right?

The ocean. The candles. The sunset.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

I can hear Whit typing away. I can see the texture of the light changing on my tree, outside my window, as the sun comes up. Here comes another day. What an outrageous, incandescent blessing that is, isn’t it? I have never lost sight of that. I hope I never do.