I was thrilled when Sere Prince Halverson, whose wonderful blog I’ve read for a long time, sent me an advance copy of her first novel. The Underside of Joy, which is available here, is a beautiful story about love in all its myriad shapes and about all the ways that people can be knotted together as family. Sere’s voice is lyrical and lovely, and The Underside of Joy kept me up way too late in my sister’s apartment in Jerusalem. I was utterly engrossed in story and deeply invested in the main characters.

Within the first few pages, the protagonist, Ella Beene, is widowed, left alone with her husband Joe’s two children. Ella has known Zachary, now 3, and Annie, now 6 for three years, since she met their father and almost instantly merged into their family. When Ella meets Joe and his kids, their mother, Paige, had left four months earlier, in the throes of a deep postpartum depression. It becomes clear as the story goes on that Ella and Joe both stayed willfully blind to the complexities of Paige’s potential return. We begin to see, in fact, that Joe’s turning his back on the situation was more than just wishful thinking; it was cruel.

Ella is left with – literally – buried boxes and hidden envelopes full of Joe’s secrets. She unravels the truth of Paige’s story even as Paige herself comes back, claiming Annie and Zachary in small and then large ways. My sentiments were originally entirely with Ella, and yet as I learned more about Paige, about the way Joe rebuffed her sincere efforts to return to her children, about the depth and severity of her depression, she became a sympathetic character in her own right.

The Underside of Joy explores the nature of family but also the meaning of home. Ella herself had slipped into Joe’s world completely, leaving behind an unhappy marriage filled with the stress of infertility treatments and poor communications. She finds herself in Northern California, whose particular geographical contours, arching redwood trees and rocky coastline, are powerfully evoked, and inside a family whose warm embrace feels like home. She – and, we learn later, Paige – comes from a family with secrets of its own, which makes it impossible for her to unequivocally judge Joe for the decisions he made. In fact, Ella learns of herself: “There was now the undeniable fact that I’d lived much of my life according to that one lesson: Look the other way. Don’t ask. Ever. And good God, don’t say what you really think.” But what The Underside of Joy traces, ultimately, is Ella’s learning to look into the blackness. And to say what she really thinks.

As Ella learns to ask, to say, to look, she probes the deepest recesses of the human heart. How do you define mother? It is not, we understand, fiercely, merely a matter of blood. What does loyalty mean, and how do you parse and order those various allegiances when they are in conflict? How do we reconcile the devoted love we had for someone who died with the ambivalent legacy he left?

Sere is unflinching in her ability to draw complicated, deeply human people. Everybody stumbles, she asserts, and the best we can do is turn and face our flaws. Joe, whose spirit haunts the book, is revealed over and over as someone who preferred not to see the ugly marks, the scars, the messiness. Though we can understand why, and Ella’s response to him is never simplified into frank blame, I can’t help feeling that he is the least likeable person in the book. Maybe that’s not fair, because he can’t defend himself. But it is his inability to face the bleakness at the center of those he loves most that leaves both Ella and Paige stranded in a tangled emotional forest. That said, The Underside of Joy refuses to resolve into easy answers, into good and bad. In the epilogue, Ella looks at Annie and thinks:

What I want to tell her, but what she will have to discover on her own, is that no matter what she chooses to do for her profession, she will save people, and she will also do people grave hard – and they will be the same people, the ones she loves.

There are other subplots to The Underside of Joy, all of them involving legacy and history, the ways our history haunts us for better or worse throughout our lives. The novel’s message echoes: we cannot escape where we came from, but those shadows provide immeasurable depth to the joy of our lives. The Underside of Joy‘s last paragraph contains these lines, which are so familiar to me that my eyes filled with tears as I read them and my heart thudded with recognition:

I know now that the most genuine happiness is kept afloat by an underlying sorrow.

I cannot recommend The Underside of Joy heartily enough: it is a novel that is as moving as it is entertaining, and I absolutely loved it.

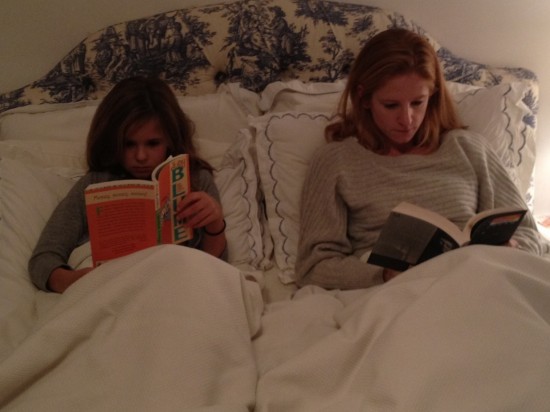

photo taken on Saturday late afternoon

photo taken on Saturday late afternoon