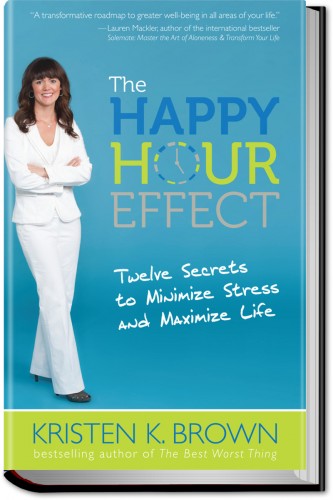

I am delighted to be participating in a blog tour to celebrate the release of Kristen Brown’s book, The Happy Hour Effect: 12 Secrets to Minimize Stress and Maximize Life. Kristen, an author, entrepreneur, certified health coach, mother, and widow, has written an practical guide to reducing stress and increasing joy. Her book includes actionable steps, inspirational quotes, expert interviews, and anecdotes which together provide an appealing and specific approach to change our lives now.

We are hurtling headlong into a season that many find taxing and overwhelming. Last year a dear friend asked me for advice on how to reduce what felt like immense mayhem and pressure around the holidays. Though I have made changes in my own life to try to protect this season as one of peace and reflection, the truth is I was at a loss for what to say. Thankfully Kristen has written a short piece with 10 instant holiday stress busters. I am happy to share this pragmatic advice here.

10 Instant Holiday Stress Busters

The holiday season is upon us and with it comes gift-giving, entertaining, parties, kids’ events, travel and weather issues, emotional overload and many other stressors that can overload us. As a widow mom, entrepreneur, writer and speaker on all things work/life harmony and stress management-related, I have pulled together 10 of the most simple, effective ways to reduce the symptoms of holiday stress (or everyday stress). Each one takes just seconds to do and they have been scientifically-proven to help our bodies and minds function more effectively! In moments you will feel less anxiety and more balance with some nice health benefits as a bonus. Check out the list and try each one when holiday craziness overcomes you.

- Breathe deeply.

- Spend time with your kids.

- Do something nice for someone else.

- Sip green tea and grab a healthy snack.

- Take a walk or run.

- Take a nap.

- Play with your pet.

- Meditate.

- Hug someone.

- Let it go and walk away.

Another tip that deserves its own mention is to put yourself in others’ shoes. Would you rather receive a gift card or a gift you don’t want no matter how thoughtful? Would you rather enjoy a laid back holiday party or a super-formal gathering? Do you prefer simple, traditional decorations or over-the-top glitz? Do you want your kids to value human connection and the spirit of the holidays or to learn self-indulgent materialism and over-the-top spending? Once you realize that your stress may be caused by over-complicating something that should be about peace, joy and love, you and your loved ones will be much happier and healthier too!

Kristen K. Brown is a bestselling and award-winning author, widow mom, speaker and founder of Happy Hour Effect. Check out her books “The Best Worst Thing” and “The Happy Hour Effect: 12 Secrets to Minimize Stress and Maximize Life” at www.HappyHourEffect.com.