First birthday, 2003

First birthday, 2003

Second birthday, 2004

Second birthday, 2004

Third birthday, 2005

Third birthday, 2005

Fourth birthday, 2006

Fourth birthday, 2006

Fifth birthday, 2007

Fifth birthday, 2007

Sixth birthday, 2008

Sixth birthday, 2008

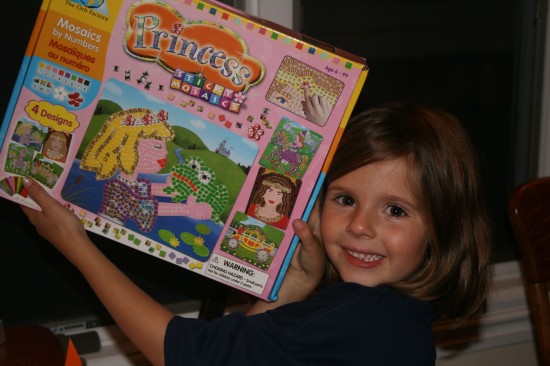

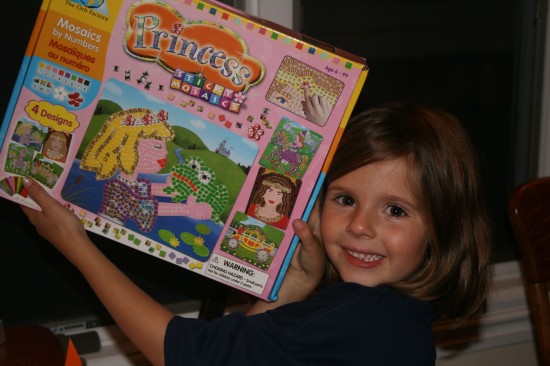

Seventh birthday, 2009

Seventh birthday, 2009

Tomorrow … eight. How is it possible?

First birthday, 2003

First birthday, 2003

Second birthday, 2004

Second birthday, 2004

Third birthday, 2005

Third birthday, 2005

Fourth birthday, 2006

Fourth birthday, 2006

Fifth birthday, 2007

Fifth birthday, 2007

Sixth birthday, 2008

Sixth birthday, 2008

Seventh birthday, 2009

Seventh birthday, 2009

Tomorrow … eight. How is it possible?

“I have just begun to accept the relentless flux that is the condition of my life, of all our lives. Not young, not old; not betrothed, not alone; thinking back, looking forward; not broken, not quite whole anymore, either. But present.”

“I have just begun to accept the relentless flux that is the condition of my life, of all our lives. Not young, not old; not betrothed, not alone; thinking back, looking forward; not broken, not quite whole anymore, either. But present.”

-Dominique Browning, Slow Love

From the lovely blog Slow Love Life (also by Dominique Browning). Thank you, Robin, for sharing this marvelous site with me – I feel I have found a kindred spirit for sure.

Mary Oliver’s words about writing poetry with a pencil – so you could see the words that underlay the final words – made me think about pentimento, and I’ve been musing about that word ever since. I had my own experience of pentimento, sitting there in the Wellesley chapel, because sitting beside my mother and me was a woman who has known me since birth. She is part of the extended family who was such an integral part of my childhood. That woman, a beautiful, serene person who radiates calm, is woven tightly into the fabric of my childhood.

She’s known all of the Lindseys who came before the Lindsey I am now.

The toddler with a bowl cut, the short girl with messy red braids, the bossy high schooler who forced all the other children into performing Circle Game wearing all white, the fellow mourner at Susie’s funeral, the bride, the new mother, and on, and on. She knows – as does my mother, of course, sitting right next to me – all of the faces that are layered underneath the face I have now.

We are all composites. We are made of all that has happened to us and all we have made happen. Of the people we have loved dearly, those we have lost painfully, those who still walk beside us. Of all of our erased words, our painted-over images, the things we prize and the things we aim to hide. This is what I loved most about Darin Strauss’s gorgeous memoir, Half a Life: the examination of the way that who we are is made up of what has happened in our lives.

I’ve written before about the mute indifference of space, about how baffling it is to me to be in physical places that hosted important moments, and to feel as though somehow the space is just blank, empty. It seems as though the place should still hold a shadowy remnant of what happened there. I know inside of me there are certain events and people who, though long gone, beat on, steady as a pulse.

Similarly, certain freeze frame memories of who we were at specific moments seem more vivid than others, their imprint more visible on the palimpsest of our souls. I’ve had moments with friends I’ve known intimately for a long time where all of the people they’ve been to me flash across their face. These experiences reinforce the depth of a many-year bond. I wonder if, when we think back on the pentimento of our own spirits, the images that rise up are the same ones that those who have known us longest see?

What I know for sure is that the irrefutable beauty of a person is in this texture. What fascinates me about people is the way that who we were peeks around the corners of who we are now, informing it in ways both visible and not, and that we are not, in fact, immutable, but always changing, buffeted and shaped by those people and events we draw into our lives.

I never thought I’d compare oxbow lakes to pentimento, bring geography and art history into close adjacency, but the echo seems impossible to ignore now. As I wrote in January, “As moving water marks the earth, so does time mark our spirits. Minutes add up to months, and months add up to our lives. And as they do, they indelibly shape and mark us.” And that passage is visible, if we look closely, underneath the surface of each of us.

My mother and I went to hear Mary Oliver read last night. She read in the chapel at Wellesley College, which was full to capacity – hundreds of people, standing room only. Katrina had described Mary Oliver as “elfin” to me and she is. Tiny and sparkling at the same time, wearing plain black, she commanded the entire room from her spot at the front of the room. The crowd was spellbound, mostly silent, but occasionally breaking into murmurs of emotion, particularly at familiar poems like Wild Geese.

The silence in the chapel had a tangible quality to it, like reverence, or grace. Through the window behind me I could see the sunset, and I kept looking back, watching the sky grow more and more glowingly pink, sliced as it was into small pieces by the dark-wood-detailed window panes. It was the kind of sky that I recently told a friend makes me believe in God, where the clouds are lit from beyond the horizon, by beams from a world beyond the curve of the one we live in.

Watching the incandescent world, the fall leaves blotted against the sky, alive with beauty, and hearing Mary Oliver read her words about ways that holiness inhabits the natural world, I felt something substantial settle deep inside me and something billow to life at the same time. Somebody in the audience asked Oliver what the role of beauty in the world is, and she replied, simply, “Beauty gives you an ache to be worthy of it.” And that was precisely what I was experiencing, right then, with the sunset and the words and the ineffable quality of the silence in that chapel.

Someone else asked her about her childhood, and whether she writes much about it. She laughed briefly, and then said she had not written much about it but planned to. She said, then, that she had not wanted to write about her childhood until she “took true title of her life.” This phrase has been with me for hours: isn’t that what I’m engaged in, here, in some ways? Taking true title of my life, assuming ownership of my experience, growing comfortable asserting my own mastery over my own story?

One other question struck me: asked what physical conditions she writes best in, Oliver said that she writes often outside, always with paper and pen. She said you can’t write poetry on the computer, because when you change a word you need to erase it and write over it. This brought to mind the notion in painting of pentimento, and I wondered how it might operate in poetry: all the words that were thought of before exist, erased but still faintly visible, on the page beneath the final word. What texture this provides to the final verse. Is this true of our lives, too? Do we still have, running through us, all the versions of us that preceded who we are right at this moment? Aren’t we all made up, after all, of layer upon layer of personality, experience, loves, losses, the accumulated detritus of our years on earth?

Oliver read an assortment of poems, some old favorites and many from her new book, Swan. I loved one new of her poems the best. The room rippled with emotion, faint gasps, and wide-eyed wonder as she read the final line. I share the poem in its entirety here.

Whispered Poem

I have been risky in my endeavors,

I have been steadfast in my loves;

Oh Lord, consider these when you judge me.

I was privileged to attend a reading/discussion last night with Dani Shapiro and Darin Strauss, talking about the art of memoir. I had just finished Darin’s fantastic memoir, Half A Life, and we all know I’d walk to the ends of the earth for Dani. The event was fabulous – my super-incredible writer friend who came with me even said it was probably the best writer’s event like this she’d ever been to.

Dani reviewed Darin’s book for the New York Times, which she’d mentioned to me, so I was predisposed to like it. But. Wow. The book took my breath away. It is a spare, short, searing meditation on how what it means to live a life. Darin, at the age of 18, was involved in a car accident that resulted in the death of a girl he went to school with. Cleared of all guilt by the court systems, he spent the next 18 years trying to bury the accident, to get “over it.” Finally, after writing three successful novels, he said last night, he realized this experience was getting in the way of his fiction. He decided to write about it, initially just for himself, and it turned into this book.

Go, now, and buy this book. You will read it in a day, turning the pages hypnotically, as I did. I think the brilliance of Darin’s book is his ability to generalize from a very specific and tragic occurence to a much more universal human question: how do we live with what happens to us, and with what we do? How do we incorporate the small and big moments, those anticipated and not, into the fabric of who we are?

It was a larger and more complete moment than simply the words that were like whitecaps on the surface of it. All moments are like that. But the rare thing is to have a clear sense of this depth, and to know another person is sensing it, too.

Darin writes gorgeously about the moments that define our lives, both in the living of them and in the ways that they reverberate, both forward and back. Dani referred, last night, to samskaras, which is one of the most powerful motifs of her book for me, and one that I had in mind a lot while reading Half a Life. Samskaras are the moments, people, places, and losses of our lives that harden into little knots around which the river of our consciousness learns to flow … these little hardened rocks alter forever the path of our lives, perhaps imperceptibly, perhaps not. Over time, as we know, a slight arc in a stream of water cuts into the bedrock beneath it, and we are changed irrevocably.

Half a Life explores this question: how do the things that happen to us shape our lives? What arcs and shapes does chance, and luck, and happenstance carve into who we are? We can’t know these things as we live them, and their ramifications play out over years, unfolding like a slow motion Jacob’s Ladder. But the path that they trace is, in retrospect, understandable. And there is power in this kind of mapping.

Darin speaks in his book about something he touched on last night as well: the performative aspects of grief. I think this can also be extrapolated into the performative aspects of reality and life itself. He says “I kept waiting to become more who I thought I should be,” with specific reference to the grieving boy in this story, but can’t we extend that sentiment to all of us? I often have the sense that I am watching myself go through my own life, inhabiting a series of masks that are predefined and predetermined; the act of this is soul-draining, and Darin excavates what this feels like beautifully.

Ultimately, Half a Life isn’t about getting over tragedy, about closure, or about moving on. It’s about acceptance, forgiveness, and humanity. It’s about owning our own childhoods, our own trajectories, replete as they are with love, hurt, mistakes, and grace. It is about learning to walk our own paths, and incorporating what happens to us as well as what we do to others along the way. This book is about nothing less than what it means to live in this world, and I can’t articulate how it moved me.

It is fitting that some of Darin’s last lines refer to T.S. Eliot, the poet whose words so many readers have sent to me. This is what Half a Life is about. And I can’t recommend it highly enough. Go, go, go, go now. Read it.

Things don’t go away. They become you. There is no end, as T.S. Eliot says, but addition: the trailing consequence of further days and hours. No freedom from the past, or from the future.