We went to Hawaii over Kauai for spring break. For obvious reasons, we did not plan our trip during the fall as we usually do. For other obvious reasons, I did not have the usual lots of planning/air BNB/adventure in me. I am sure we will go back to Europe, but for now the whole continent reminds me of my father in a way I can’t sign up for. So we went to Hawaii. None of the four of us has ever been, and truthfully, I’ve always wanted to go. We chose Kauai because we’d heard it was the quietest, most rural island, and that sounded about right. The trip there was long (booking six weeks before travel, on miles, means you don’t get the most direct or convenient flights).

We arrived in Kauai on Tuesday afternoon. It was gray and spitting rain, but we were thrilled to be there and the children ran right to the ocean. On Wednesday morning we woke up to torrential rain. Our phones vibrated with flash flood alerts. The concierge at the hotel said they hadn’t had rain like this in years. The forecast was for three days of torrential rain and maybe a peek of clearing on Saturday (we were leaving Kauai on Sunday morning). I had a moment of: can’t we get a break? we just wanted something to be smooth and relaxing. But I tried to shake off my grumpiness, and we headed to where we always go when we don’t quite know what to do: the bookstore.

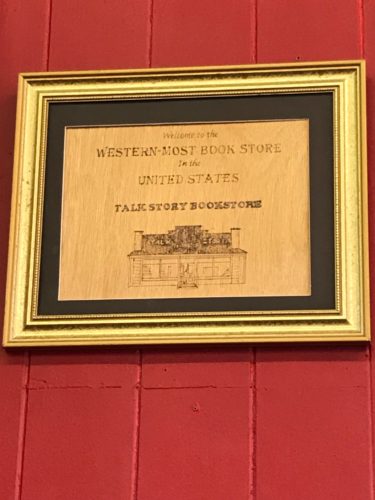

The western-most bookstore in the United States, to boot! Talk Story sells both new and used books, and the smell when we walked in reminded so much of my father I was almost brought to my knees. Everybody bought a book, and we found a cute place for coffee and acai bowls, and I was glad we brought raincoats. I woke up the next morning and lay in bed, listening to a constant whirring sound. “Is that more rain?” I asked Matt, distressed but resigned.

“No, Linds, it’s the air conditioner.” He replied. I jumped up and pulled the curtains, and saw that it was gray but not actively raining. Delightful. We spent most of the day at the ocean, and the kids took a surfing lesson. The sun actually came out.

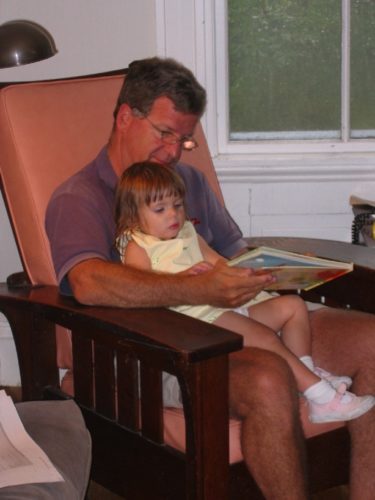

My favorite experience of our Hawaii trip was the three afternoons we spent floating in the water together. The waves were big and rough, and we let them toss us around. Grace, Whit and I had a long conversation about how when the waves get really big the best bet is to drive through them. The only way out is through. True in life, too. I told both children about how when I was in labor with them, I envisioned waves, and I thought about this particular adage: through. Through to the other side. Lean into the wave. It strikes me that while my childbirths were long ago now, that advice is still good today.

Another day, we went zip-lining. The landscape was spectacular, and all four of us tried it in the “flying” position as well. Grace and Whit were the most fearless and also ziplined upside down. The scariest part of any zipline, we all agreed, was the leaning into thin air from the platform. It’s the jumping off. This is true, also, of life itself.

We also went for a beautiful hike along a ridge by the ocean. We could see humpback whales leaping and spouting in the ocean. The landscape was rocky and foreign and gorgeous.

We saw sunsets (below) and sunrises (below that). By “we” I mean Matt and me, as Grace and Whit slept long and hard. Kauai was as magical as we had been told. The island felt relaxed and joyful, and strange coincidences made us both feel our fathers near. A song that reminds Matt of his father was playing seemingly everywhere we went. And we saw dozen of KCM (my father’s initials) license plates in Kauai. Yes, all the plates there start with K. But still. Everywhere I turned I kept seeing KCM.

The first couple of days were rocky, and we had some family arguments I’m not proud of. But once we found our groove, it was lovely: we ate well and slept well and rested well and felt the sun on our faces. The difficult first days reminded me that all four of us have, individually and collectively, been through a lot these last several months. We are still limping. The losses, and their aftermaths, are still fresh. I think forgiveness and patience is called for.

Forgiveness. Patience. Two things I’m not good at, giving or receiving. But the waves are big, and the only way through is to lean into them, with forgiveness and patience. And some deep breaths.