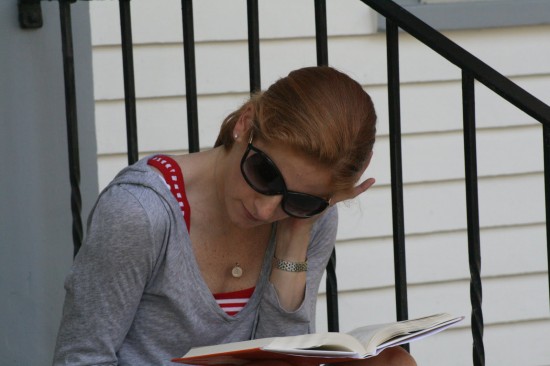

Last summer, at BlogHer, I saw Stacy Morrison across the room. She was getting ready to sign copies of her new memoir, Falling Apart in One Piece. She looked happy, masterful, confident, and I remember thinking: she seems really cool. Little did I know. She is definitely cool! And I adored her memoir, Falling Apart in One Piece, which I read last week and loved. I wept, I laughed, I underlined, I read aloud to my husband, I tweeted quotes. Generally, I did all the things I do when a book truly speaks to me. And this one did.

Falling Apart in One Piece is, at first glance, a memoir about divorce, but I think its message is also much more broadly relevant. Essentially, the book is about what happens when life doesn’t turn out the way you planned and expected, and about how thoroughly that reckoning can dismantle your sense of self. I certainly have been through these choppy waters myself, as have most of the people I know. The triggers and circumstances that lead us into the rapids differ for each of us, but I think there is tremendous universality in the lessons. This is the power of Morrison’s book.

Falling Apart in One Piece begins with a relatively brief description of Morrison’s childhood. Her portrayal of her mother moved me the most. “I thought she possessed magic, even though she also carried so much sadness,” she says, brilliantly evoking the woman whose strong pull on her continues into her adulthood. Perhaps in response to her mother’s sadness, Morrison develops a “big personality” and a strong instinct for being in control. She describes falling in love with her husband, Chris, and the authenticity of their feelings comes through vividly. She lets down her guard for Chris, calling him “the person who knew the scared, sad girl who lived inside me that I didn’t let anyone see.” They marry young and, in many ways, grow up together. Despite Morrison’s stubborn independence, it is clear that Chris and she are utterly intertwined.

It is only when their marriage ruptures that we see the extent to which Morrison’s sense of self was also intertwined with Chris. The part of Falling Apart in One Piece that traces Morrison and her husband’s stop-and-start, stuttering efforts to save their marriage are among the most humane and realistic descriptions of an adult relationship I’ve ever read. We see how deeply they love each other, but we also see the deep grooves they’ve each worn into each other. Falling Apart in One Piece reminds us that deep love and lots of effort is not always enough to save a relationship.

That sounds cynical and depressing, but this memoir is absolutely neither of those things. There is a deep and abiding optimism at the heart of Morrison’s story (in fact “one optimist’s journey through the hell of divorce” is the book’s subtitle). Certainly, though, we watch her fall apart completely, a collapse that was triggered by having to let go of the way she thought her life was going to be, and by learning that the person who had defined her for so many years was not only gone but also, possibly, wrong about her in essential ways. She has to learn to trust her own voice in her head rather than hearing Chris’s.

Even in the darkest months of her life, the times when she is least sure of anything, Morrison has moments of startling peace and, even, joy.

As I looked at the mosaic floor my son was joyously dancing on, I was reminded that what you see in your life isn’t one thing one picture, one thought. Life is a thousand little pieces, sliding and moving, like bits of glass in a kaleidoscope. You may get a moment of suddenly taking in a pattern whole, and then it’s gone again in a flash, changing, shifting into something else.

Morrison also shares scenes of emotional disintegration that took my breath away their intimacy and their familiarity. She lies on the floor of her kitchen, weeping, “in full submission, a circumstance I had spent my whole life furiously fighting to avoid,” forced to stare her own fragility and fear directly in the face. Morrison endures sieges from both rain and fire that are biblical in nature and scale. The metaphor is impossible to avoid: every single atom in the universe seems to have joined in the chorus telling her that she is not in control.

Morrison’s indomitable spirit carries her through these disasters and keeps her moving forward. As her son grows into a cheerful toddler he, too, begins to act as a cord tugging her forward, out of her sadness and fear, into the moment that is right at her feet. She finally sells the house with the flooded basement and the memories of her marriage ending, and moves to a new apartment and a new life. She tiptoes onto firmer land, begins to realize that the negative way that Chris (and, importantly, she) saw herself at the end of her marriage is not, in fact, the ultimate judgment on her character, starts to see the potential of a family configured differently than she had imagined. Even so, the waves of sadness and difficulty continue.

I needed to continue to find the way to make peace with the challenges of the way every day contained a little sad and a little good, the way grief was a constant undercurrent to my moving-forward life.

I need to write these lines on an index card and put them above my desk (right next to Wendell Berry’s The Real Work). This is the work of my life right now. Morrison goes on to reflect on her flooded basement, noting “I realized now that my soul had been carved deep to take in life’s water,” and I gasped, thinking of my own reflections on how my propensity for great sorrow and hurt is inextricably correlated to my immense capacity for wonder and joy. Yes, yes, yes.

Even as she moves forward in her life, settling into new patterns and rhythms, Morrison finds herself occasionally blindsided with grief, shocked with a sadness she thought she had processed and moved past. She expresses frustration that she is not “finished with this crushing grief” yet, describes with resigned awareness “this continually appearing astonishment that life could hurt so much and that I could be so unprotected.” Morrison’s refusal to wrap her story up in a neat happy-ever-after ending is part of what I love best about this memoir: it is honest, and real, in its description of grief’s winding course, in its assertion that a human being growing into herself is a decidedly non-linear enterprise.

I underlined furiously in the last couple of chapters of Falling Apart in One Piece, finding many beautiful reflections on life that rang inside my chest like a deep gong. I can’t possibly share them all, so I will close with my favorite. I urge you to read this book. Morrison’s memoir is beautifully written and powerfully captures what I believe is a fundamental task of growing up as human beings: letting go of what we thought it was going to be in order to embrace what is. What Morrison realized, and shares gorgeously, is that between the letting go and the embrace is a freefall, both liberating and terrifying. I am living in that freefall right now, experiencing its wild freedoms and overwhelming fearsomeness on a daily basis.

That I believe in the power of love. That I believe that life is worth living. That I believe it is just as likely that there is something good, something amazing, waiting for me around life’s next corner as it is that there is something terrible. I expect some of both, frankly.

Also, check out Stacy’s fabulous blog, Filling In the Blanks, which has swiftly risen to the top of my daily reads.