June 9, 1943 – November 26, 2017

Remembrance from my father’s memorial service, December 3, 2017

I am Lindsey, Kirt and Susan’s older daughter. Thank you for being here today to celebrate my father’s life. There is a line in Steinbeck’s East of Eden in which the characters lament the coming death of their beloved father. How could they think of anything without knowing what he thought about it? This is exactly how I felt about my father my entire life. All that mattered was what he thought. Dad’s has always been the voice I hear in my head, and I suspect – and hope – that never changes.

Dad was, as we said in the obituary, a Renaissance man. He was a man of towering intellect, occasional gruffness, and, perhaps, less well-known but equally importantly, hilariously apt one-liners. Two that come to mind for me often are his assertion that “there are two words that separate us from the animals: may and well.” I have taken that particular adage to heart and think of it every time my children respond to “how are you?” with “I’m well.”

Another thing Dad said often that’s come to mean a lot was his repeated comment to his daughters: “I’m sorry, you must be mistaking this for a democracy.” As a child, of course, that sentence drove me nuts. As a parent, I think he was onto something.

Dad had unapologetically high standards. When I graduated from Princeton magna cum laude, his first words to me were “what happened to summa?” Sometimes his demand and expectation of excellence felt onerous, but most of the time it inspired me. He was invariably curious about my life – asking each and every time I saw him about Grace, Whit, and Matt, the new company I founded this year with wonderful partners, and my writing, usually in that order. He told me often, and recently, how proud he was of Grace and Whit (the expression he used, just last week, was “is there anything they can’t do?”). It’s a gift to be so certain of his love and esteem, and I know it.

My father was an engineer. He had a master’s degree in Physics, a PhD in Engineering, and an abiding trust in the ability of science, logic, and measurement to explain the world. At the same time, he had a deep fascination with European history and culture, often manifested in a love of the continent’s cathedrals. His unshakeable faith in the life of the rational mind was matched by his profound wonder at the power of the ineffable, the territory of religious belief and cultural experience, that which is beyond the intellect.

I grew up in the space between these worlds. This gave me an instinctive understanding that two things that appear paradoxical, like these beliefs, can be both totally opposed and utterly intertwined. From my father I learned that at the outmost limits of science, where the world and its phenomena can be understood and categorized with equations and with right and wrong answers, there flits the existence of something less discernible. The finite and the infinite are not as distinct as we might think, and the way they bleed together enriches them both.

My Dad, who had a three-ring binder full of mathematical derivations he had done for fun (in fountain pen), also stood next to me in cathedrals in Italy, looking up at stained glass windows with frank reverence on his face. For all of his stubborn rationality and fierce belief that everything can be explained, he also always suspected, I think, that some things could not. In fact I think for my father, despite how trained and steeped he was in the language of equations, proofs and derivations, the parts of the human experience that cannot be captured by the empirical were the most meaningful.

This contradiction existed in how he thought about sailing, too, the other primary through-line of his life. Sailing was about careful navigation, measurement, and the angles between water, sail, and wind. And yet at the same time sailing was for Dad about something far less tangible, a fleeting and effervescent way of being in the world, an ability to sense and feel the boat and to make infinitessimal adjustments that made the boat move more smoothly and faster. I often told Dad that he was the person with whom I felt safest on the water, and this is true despite some very bumpy sails. His favorite point of sail was to windward. There was both precision and something far greater guiding my Dad’s hand on the tiller.

There are so many things Dad taught me that I can’t possibly list them, but this was his greatest gift: the belief that there is meaning beyond that which we can prove, and that a life of celebrating that can be a rich one indeed.

Dad often quoted Peter Pan, and his cry “Second star to the right, and straight on ‘til morning!” Dad’s with the stars now, and I’ll remember that every time I look up at the night sky that he so recently explored with us. I think of Grace, Whit, and Dad standing in the street in Marion viewing Venus when it was visible two summers ago. One of my dear friends from college emailed me after Dad died about how he was “part of the firmament,” as a way of conveying her shock at his loss. I loved that image, and one morning this week driving to the bus I asked Whit to look up the formal definition of firmament. It is “the heavens or the sky.” So I think he’s still – maybe even more – a part of the firmament now.

I wish you fair winds and following seas, Dad. And I thank you.

***

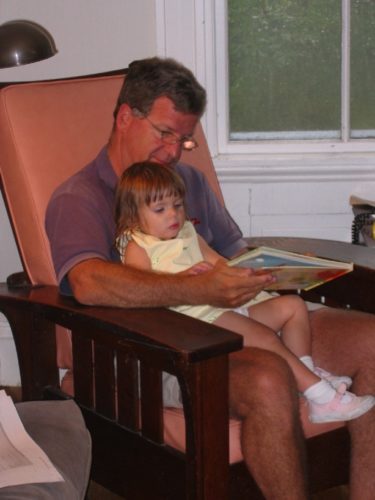

Two photos of my children and my father that I love